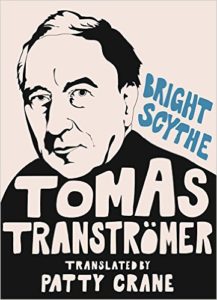

Bright Scythe, Selected Poems

by Tomas Tranströmer,

by Tomas Tranströmer,

translated by Patty Crane,

Sarabande Books, 2015,

240 pages, paper,

ISBN: 1941411215

Buy the Book

Sweden’s great poet, the 2011 Nobel Prize winner, Tomas Tranströmer (1931–2015), produced a relatively spare and exquisite oeuvre over the course of his life. He published his first works at age 23, and proceeded, with great regularity, to produce numerous slim volumes of poems over the following fifty years. During that time, he balanced writing with his work as a psychologist and his family life. He also found time to become an accomplished pianist (playing concerts and recording a CD) and an amateur entomologist. In 1990, Tranströmer suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed on his right side and impaired his ability to speak. He continued writing, with great and increasing difficulty, publishing two more books of poems and a memoir, and trained himself to play piano with only his left hand.

Tranströmer is a poet of borders, boundaries, and thresholds. Always crossing and re-crossing, his was a restless intelligence that challenged supposed dichotomies of space and time, the conscious and unconscious, penetrating barriers and rendering them much more murky and mysterious than previously assumed and, in a sense, less clear and more gray, in the way we know life really is. The poems contain countless occurrences of dreaming and waking, thresholds between life and death, and boundary markers in the human and natural landscape: the edge of a forest, a half-open door, a window. Vehicles in the poems transgress and move through these boundaries: trains, cars, vans, and boats carry the speaker and reader through liminal spaces.

Translation, too, is a process that crosses spaces and challenges borders. And much like Tranströmer’s poems, it permits us, notes Edith Grossman in Why Translation Matters, “for a brief time to live outside our own skins, our own preconceptions and misconceptions. It expands and deepens our world, our consciousness, in countless, indescribable ways.” Translation allows us to experience the “otherness” within ourselves and in our own lives, not unlike the uncanny otherness that Tranströmer cultivated in his poems. And nowhere is that understanding more prevalent than for the translator herself. “I felt as if I were discovering a third language where English and Swedish intersected,” says Patty Crane, “And that language is mirrored in the poetry itself, where the boundaries between inner and outer landscapes — the psyche and the world — seem to shift, open and somehow merge.”

One of Tranströmer’s first poems, published in 17 Dikter (1954), is “Stones.” May Swenson translated the poem in 1972, Robin Fulton’s translation of Tranströmer’s entire body of work was first published in 1987 (and updated in 1997 and 2006 subsequently), and Patty Crane has again translated the poem here. The differences between these translations are not small, and have to do with when and how the action is occurring — verb tense — as much as with sentence construction or word choice. Swenson’s translation begins: “Stones that we have thrown I hear /falling, glass-clear through the years.” The opening line of Fulton’s translation begins, “The stones we threw I hear /fall, glass-clear though the years.” And Crane’s: “The stones we have thrown, I hear /fall, glass-clear through the year.” Fulton’s phrasing seems to direct the throwing of specific stones to a very specific time, whereas Swenson’s and Crane’s choice of the present perfect locate the action in the unspecified past. In all cases, the speaker continues to hear the stones “glass-clear,” a hybrid word chosen by all three translators, taken from the Swedish word glasklara, meaning “crystal clear.”

One of the real delights of the Crane translation is the accompaniment of the Swedish text on the facing page. It allows the reader to note the poem’s original shape and form, and to recognize relationships between the two languages. It allows us to see that the rhythm and repetition in the Swedish “trädtopp till trädtopp” and “bergstopp /till bergstopp” can be carried forward in the English “treetop to treetop” and “hilltop /to hilltop” (Fulton) or “mountain-top/to mountain-top” (Crane). Other significant differences in word choice between the translators of “Stones” include how the “confused actions of the moment” (Fulton and Crane), are “made mute” (Swenson) or “become silent” (Fulton) “in thinner air”; while they are “quieting /in air thinner than now’s” in Crane’s version. In a sense there is a difference in the agency of the air itself — air “made,” “becoming,” or “quieting” — that affects the movement and energetic arc of the poem. Crane’s deft solution allows the rhythm and tone established in the first lines to continue.

To my ear, Swenson’s is the most wooden of the three, incorporating what feel like too many excess articles and conjunctions — “in thinner air than that of the present” (my italics). But often this sort of complication belies a fidelity to the text, a direct translation. Crane’s translation seems to avoid this awkwardness while maintaining fidelity to the form. And while Fulton’s rendering of the poem falls more firmly in the past — and his translations are widely considered the most literal — Crane’s translation allows the poem to remain more temporally open, suspended in the in-between, through the use of gerunds — “quieting,” “gliding” — until the final, ending lines, “Where /all our deeds fall /glass-clear /to no ending /except ourselves.”

In longer, more complex poems, Crane’s translations remain spare and seem tightly cleaved to the form of the original Swedish. In the beautiful longer poem, “Vermeer,” Tranströmer imagines Johannes Vermeer’s studio shares a wall with the raucous world of a lively tavern; “No sheltered world . . . ” it begins. Crane’s translation moves more “comfortably” for the English reader, with phrases such as “The great explosion and the delayed trampling of rescuers, /boats swaggering at anchor . . . ” in contrast to Fulton’s: “The big explosion and the tramp of rescue arriving late, /the boats preening themselves on the straits. . . . ” Crane’s is less searching, and more directly conveys meaning. While the “making strange” — or of language may serve to engage a reader in productive tension, the contents of Tranströmer’s poems contain enough strangeness to keep us more than engaged: it is paradoxically the spareness and linguistic concision in his poems that lets us float in the wonder of his borderlands.

In “Vermeer,” the thin wall that separates the private painter from the noise of the world becomes one of the insurmountable walls in our lives; we must pass through it, yet with excruciating difficulty. And then, in the beautiful, transcendent last stanza, translated identically by both Fulton and Crane, he surprises us:

The clear sky has leaned against the wall.

It’s like a prayer to the emptiness.

And the emptiness turns its face to us

and whispers

“I am not empty, I am open.”

It is often said that a great poet deserves many translators. Tranströmer welcomed the differences his translators brought to the poems. When John Deane brazenly wrote Tranströmer regarding his impressions that previous translators — Robert Bly, May Swenson, and Robin Fulton, among others — were unsuccessful, the poet replied encouragingly and challenged him to do better. (See his translation of For the Living and the Dead.) It is my impression that through multiple translations, a community of readers learns a poet and his poems, deepening our understanding of the qualities of a unique intelligence. Through this collective project, the translations get better. Each new word choice, each grammatical moment challenged and fussed over, brings us closer to the meaning inhabiting the work. And yet, as with Tranströmer’s poems, the closer we approach, too, the further away we become. There is no “one text”; there are many texts overlapping in murky territories, these boundaries that so often falsely divide us that Tranströmer sought to transcend. Patty Crane worked closely with Tomas Tranströmer and his wife Monica for three years to craft the meaning in these carefully selected poems. Bright Scythe is an invaluable contribution to our understanding of Tranströmer’s concise and penetrating body of work.

— Julie Poitras Santos