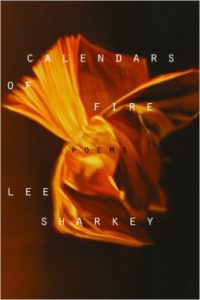

Calendars of Fire

by Lee Sharkey,

by Lee Sharkey,

Tupelo Press, 2013,

60 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978-1-936797-26-4

Buy the Book

“Why do we war on each other? This is an unanswerable question we should never stop asking,” writes Lee Sharkey in the reader’s companion to her latest book of poems, Calendars of Fire. Weaving together images from multiple wars, mythology, and personal accounts of grief, this collection of poems addresses the writer’s outrage and disbelief at a world of humans who enact violence upon one another, while also grappling with the inescapable truth we all face: mortality.

The poems often take the form of elegy, prayer, or vision. The theme of transience, introduced in the volume’s first poem, “In the wind,” creates an ominous feeling at the outset:

If you walk the same path everyday through the woods

clearing the way in your coming and going

you know when branches have fallen. Each branch downed

has a trace of the wind of descent vibrating through it.

Immediately Sharkey establishes an eerie sense of fate in this forest of “coming and going,” a barren container for the short experience of life itself. This is a timeless space where “you can read the night, the wind, the lack of it / what has happened back to happening,” a place through which every human and their ancestors have passed.

Desolate images of war proliferate throughout the second section of the book, with many poems formed in sequences of one- and two-line stanzas whose emotional and thematic strength resembles that of a ghazal. In “Hunger recounts it,” she presents the raw desperation caused by war in a scene where personal belongings and furniture are burned for temporary warmth: “Burned the books, first the history, last the poetry, page by crumpled page /No no, give that to me, a neighbor insisted,

trading Akhmatova for 2x4s from graveside crosses.” This haunting parataxis creates an unsettling and believable depiction of starvation during wartime.

Juxtaposed against this despair comes the series “Tiresias at last,” where the Greek god appears: a transgender, blind prophet who sees what others can’t. Strikingly more accessible in style and language, with shorter lines and a sensual tone, the Tiresias series offers respite from the hardship that’s come before. In a tighter, lyric narrative, Sharkey begins with a poem about his transformation from male to female, and continues with “Tiresias tells it”:

Desire is the snake that courses the body

The mouth is one door of its house, the vagina another

When you lie down you lie with the snake

When you rise up you rise with the snake

To insert a shape-shifting, sexualized being at this point in the book seems, at first, an odd choice. However, as Sharkey explains in the reader’s companion to the volume (which is accessible on her website), “All poets are at least in part Tiresias, senses attuned, listening from the sidelines; coveting vision, powerless to make that vision come to pass or prevent its coming.”

Indeed, Sharkey introduces a new strength with the sensuality and prophetic perspective of Tiresias, who, unlike humans, can see beyond the grip of war. Whereas the powerless subjects that appear in preceding poems evoke helplessness, Tiresias accepts human weakness without becoming the slave of it, as in “Seer in vigil”: “Tiresias stands in winter wind / doing nothing but stand in winter wind.” In submitting to the truth of human violence, s/he can rise beyond, redeemed by a broader knowing, as in “With birds on his shoulders”:

Violation rises like a planet

its own sound something quiet

like sliding bodies into water

Altogether, Calendars of Fire offers an evocative redefinition of what we might conceive as “war poetry.” Sharkey’s careful interweaving of language fragments and white space — to connect the personal and global — is most effective when a simple narrative emerges, and is not quite as successful in longer poems, like “Possession,” in which too many worlds and memories are merged to be easily grasped.

Her lyric becomes most clear and beautiful in section III, which presents the aftermath of war, the ruin of sacred places, charred and broken musical instruments, psychic demoralization, grace, and the rebuilding of lives. Amidst the rubble, there is “Listening”:

sleep with me now under the clouds

with your lucid eye open

What is it that I love when I

form the letter with an arc and a down-

stroke

The curve of your head,

my hand rounded to stroke it,

habitat, sphere of a new planet.

Indeed, with her keen vision, Sharkey honors the brutal suffering of the human world while still managing to seed hope for a new, more whole one.

— Kristen Stake