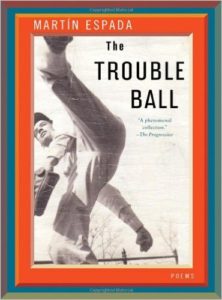

The Trouble Ball

by Martin Esapda,

by Martin Esapda,

W.W. Norton & Company, 2011,

66 pages, paper, $15.95,

ISBN: 978-0-393-3456-4.

Buy the Book

Martin Espada is no longer a legal aid lawyer in Chelsea, MA, a job that provided him with at least one book, City of Coughing and Dead Radiators. He has moved to the safe quarters of academe, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, located in what some call the “Happy Valley,” a term recognizing the Utopian initiatives in bucolic towns north of grittier Springfield and Holyoke. But Espada, whose style has always been more Springfield / Holyoke than Amherst, hasn’t gone soft. His latest poetry collection, The Trouble Ball, has plenty of his familiar punch. Some poems feel a bit ponderous in the effort to take on historical heft, but Espada retains his wise-guy sense of humor, an important tool for a writer of polemical poems, as he once observed in his essay collection, Zapata’s Disciple.

In “Blessed Be the Truth-Tellers,” he speaks of his mother warning him to “just walk away” if someone starts a fight.

Then somebody would smack

the back of my head

and dance around me in a circle, laughing. . . .

Bio notes in earlier Espada volumes have listed the variety of low-level jobs he held before obtaining a law degree. In “My Heart Kicked Like a Mouse in a Paper Bag” he recalls days on the cleaning crew at Sears:

I once removed the perfect turd from a urinal, fastidiously

as an Egytologist handling the scat of a pharaoh.

In the next to last poem of the volume, “Instructions on the Disposal of My Remains,” he says, “I want to be stuffed and mounted at the White Castle / in East Harlem.” This street-savvy

lighter touch entices readers to stay with him when he becomes more serious, as he does in “The Rowboat.”

The beggars cannot swim to the private islands of Lake

Cocibolca. Instead

they wander through the plaza in Granada, trailing after

the investors in paradise.

This is Nicaragua, where affluent tourists “climb the steps of the cathedral, to point cameras, to light candles for the dead / and ask forgiveness.” “The Swimming Pool at Villa Grimaldi” is set in Chile, where “blindfolded prisoners” are put in “cells too narrow to lie down” and taken to rooms “where electricity convulsed the body.” He writes of the “parking lot where interrogators rolled pickups /over the legs of subversives who would not talk.”

While such poems recall Witness poets like Juan Gelman or those in Carolyn Forche’s landmark volume, Against Forgetting, Espada knows that to be subversive means nothing more than expecting your apartment to be reasonably maintained (heat, hot water, no rodents) even if you only speak Spanish. This explains the irreverence he expresses towards one of poetry’s most iconic figures: “How to Read Ezra Pound” appears in part two of The Trouble Ball, appropriately titled “Blasphemy.” Espada quotes someone from a “poets panel” who recalls the Spanish Civil War:

If I knew

that a fascist

was a great poet,

I’d shoot him anyway. . . .

In “The Day We Buried You in The Park,” Espada and a co-conspirator inter the ashes of Alexander (“Sandy”) Taylor, co-founder of Curbstone Press, in an unnamed park, in violation of city law. The poem includes an epigraph from Whitman, an Espada favorite, whom he notably invoked in his earlier, much controversial, banned-by-NPR poem, “Another Nameless Prostitute Says The Man Is Innocent,” about Death Row Inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal: “If you want to see me again look for me under your bootsoles.”

Another act of civil disobedience occurs in my favorite poem from The Trouble Ball, “Isabel’s Corrido.” The 23 year old Espada enters into a marriage of immigration-convenience with a 19 year old Mexican, at the request of her sister. Isabel, his bride, has a boyfriend. It gets complicated. Eventually Isabel takes off on her own; later the sister calls to say that Isabel is dead from an apparent brain tumor. Espada recalls her headaches and no one calling a doctor: “We lived behind a broken door. We lived in a city hidden from the city.”

If Espada fans have any complaints about The Trouble Ball, it might be the title. This poet has given us “Rebellion is the Circle of A Lover’s Hands,” “For the Jim Crow Mexican Restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Where My Cousin Esteban Was Forbidden to Wait Tables Because He Wears Dreadlocks,” “A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen,” and my personal favorite, “Do Not Put Dead Monkeys in The Freezer.” The latter, both funny and chilling, recalls Espada’s job in a lab where the treatment of animals illustrates the human capacity for casual cruelty.

Regardless of titles, Espada assures us he will keep “walking through the world, soaking up the ghosts wherever I may go.” Concluding “Isabel’s Corrido,” he writes, “There was a conspiracy to commit a crime. This is my confession: I’d do it again.”

— Kevin Sweeney