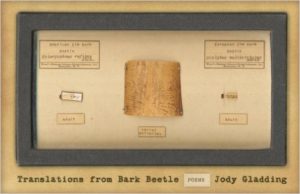

Translations from Bark Beetle

by Jody Gladding,

by Jody Gladding,

Milkweed Editions, 2014,

96 pages, paper, $12.40,

ISBN 978-1-57131-455-0

Buy the Book

We like to write on things. It’s what we do. Mostly on paper, but . . . I once got in a bit of trouble in college when I got a little carried away while chalking the campus quad for a student activist group. Maybe it was my inner Jody Gladding coming out. Whatever it was, I now regret my callow chalk self, but in that dusty moment of chalking, there was such a rush to write upon the unexpected. I think Jody Gladding knows what I’m talking about.

The poems in Translations from Bark Beetle are playful, limited and desperate. Let me explain.

In the book’s second poem, “Spending Most of Their Time in Galleries, Adults Come into the Open on Warm Sunny Days: Translation from Bark Beetle,” Gladding says, “•’ve learned through wood / yo• can only travel in one direction.” The dots are explained as translation challenges, but I just ignored them and read on, and with Gladding as guide, I too learned through wood, and stone, ice (melted), tea bags, fear (!), and liver scans, among many other things (photos in the back of the book).

I couldn’t help but feel how fun this all was, especially when I read the poem written on the icicle, which, by the time it was photographed, had melted. Gladding’s poetry is a radical mark making. These hark back to the declaratory act of chalking a sidewalk, such a physically satisfying medium, the concrete page, and then the poems transform the pedestrian into the poetic, surpassing my petty college act and moving into the realm of art. What Gladding is doing is devilishly fun, and more than a little subversive.

Such an experiment also feels necessarily limited. We place confines around us to give us structure with the hope that within restriction we find freedom, and thus surpass our limitations. This doesn’t always happen for me in reading these poems. When one is writing a poem on /in a change-of-address form, there’s literally only so much space to move around (pun intended). Sometimes these experiments feel epigrammatic and easy to dismiss. And yet, sometimes these limitations allow for true flights of beauty well beyond the physical. “Swallow,” written on a tongue depressor, is one of these:

swallow

the words

he said

we

don’t

want

them

all over

the map

of

your

tongue

and if

they

burn

the roof

of

your

mouth

we don’t

want

them

jumping

to

safety

That poem crackles. It’s fast and dangerous. “Seal Rock,” written “on split slate,” is another such poem that takes a halved stone to create one of the most beautifully sparse and lovely marriage poems I’ve ever read.

I most feel these poems are an act of desperation. It’s something I continually felt as I read the book. From “roc”: “but what if / the invisible is / simply / the unseen.” One can’t ignore that this poem was written on a feather, both a flimsy relic of flight and the archaic instrument of poetry. Gladding, in these poems, wants to bring the invisible onto the visible, to make tangible the ethereal. How could this be anything else but a desperate attempt to make sense of a cruel, dumb world? Poetry as insurance against overwhelm. What else has poetry ever been in the history of the word? What can poetry do when “we [drive] our inflated cars to our box stores and [fill] our giant shopping carts”? Jody Gladding takes our collective desperation — and my chalky regret — makes it hers, and gives it substance.

— Jefferson Navicky