Spirits in Bondage, A Cycle in Lyrics and Phantom Noise

by C.S. Lewis (as Clive Hamilton),

by C.S. Lewis (as Clive Hamilton),

released online by Project Gutenberg in 1999,

Ebook No. 2003, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2003.

Reissued in print by Cosimo Classics, 2005,

88 pages, paper,

ISBN-10: 1596053720

Buy the Book

Phantom Noise,

Phantom Noise,

by Brian Turner,

Alice James Books, 2010,

93 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978-1-882295-80-7

Buy the Book

If we ever have a true history of the Iraq Wars, it will have come from the slant of poets in the trenches, not from embedded journalists or other official spokespersons.

I was reminded of this when, looking for information on C.S. Lewis’ later fantasy writing, I came upon his 1919 first book of poems, Spirits In Bondage, in the public domain on Project Gutenberg. As a 19 year-old, Lewis was thrown into one of the most horrific battles of WWI, experienced trench warfare in one of the worst tank battles of the Somme, was wounded, saw his best friend killed, and finally returned home to care for his friend’s family. Fortunately, Lewis had one resource that most of his fellow soldiers in 1916 did not have: He could write about the horrors of battle.

In the first poem, Lewis personifies the atrocities of war he has experienced through the personage of Milton’s ruined archangel Satan:

I am Nature, the Mighty Mother,

I am the law: ye have none other.

I am the flower and the dewdrop fresh,

I am the lust in your itching flesh.

I am the battle’s filth and strain,

I am the widow’s empty pain.

I am the sea to smother your breath,

I am the bomb, the falling death. . . .

The poems that follow record young Lewis wrestling with the fallen archangel for nothing less than his soul, and those of his fellow soldiers. I very much recommend this text, a free download from www.projectgutenberg.com. Those interested in following Lewis’ mythological trail might read these poems as a roman à clef of his early career.

The casualties in the Somme were horrific. According to John Keegan’s A History of Warfare, the British Army lost 20,000 men on first day of the Somme, July 1, 1916. Lewis was a part of a battle in which machine guns fired six hundred times per minute and killed a thousand-man British regiment in an few minutes. Lewis’ poems directly absorbed the shock of his experiences of trench warfare, atrocities, post-traumatic shock, and reentry into society.

In the most recent wars, I find the American poet Brian Turner confronting war no less earnestly than Lewis did. Over half of Turner’s poems were written in Iraq, at a time when American casualties were flown home under covert conditions. Turner could not keep the battle events at as much of a literary distance as Lewis could; he works in a very different way than Lewis, the mythologist who clothed his experiences in fantasy and myth. In contrast, Turner is a realist, in the sense of Stephen Crane, constantly peeling away layers of experience until he gets to what is real.

His first book, Here, Bullet (Alice James, 2005) was a shot heard round the world. There is nothing between this poet and the bullet, directly addressed to him. Some considered it the first shot in the peace poetry movement. I did not. Poetry cannot stop wars; it can only get us closer to the truth of them. For a long time after encountering these poems, I read no newspaper and listened to no nightly news. This news from Brian Turner in the trenches was not only the truest news I had of the Iraq War; it was the only news. And it holds up well after three years, preserving the landscape of this unfortunate war with bone – chilling accuracy through the voice of a soldier’s deepest reflections.

Brian Turner’s second book, Phantom Noise (Alice James, 2010), is an even more confident collection. Here, the personal wrestling with war and belief is much more in the foreground than Lewis’ struggle was. The book begins with a series of traumatic flashbacks in the longest poem of the collection, called “At Lowe’s Home Improvement Center.” These flashbacks were well known in my own family because my father suffered shell shocks, as they were then called, after World War II. I recalled witnessing them when I encountered Turner’s description of a flashback in progress:

Standing in aisle 16, the hammer and nail aisle,

I bust a 50 pound box of double -headed nails. . . .

In a steady stream

they pour onto the tile floor, constant as shells. . . .

Turner’s poems shine light on key issues that will not go away. “Insignia,” a poem for women sexually molested by their own superior officers, is both sad and horrifying. The epigraph takes dead aim at the reader and refuses to let us wander from the statistic that “[o]ne in three female officers will experience / sexual assault while serving in the military.” Without letting the reader turn away, the story begins its own unfolding:

She hides under a deuce n’half this time — sleeping

on a roll of foam, draped in mosquito netting.

It goes on to address her terrorizer:

It’s you she’s dreaming of, Sergeant — she’ll dream of you

for years to come. If she makes it out of this country alive,

which she probably will. You will be the fire and the

hovering

breath. Not the sniper. Not the bomber in the streets.

As often happens in Turner’s poems, the one about to assault and the one about to be assaulted respond within the hair-trigger constraints of combat. Lewis, too, has poems that suggest the molestation of civilians by his fellow soldiers. Like Lewis, Turner takes the side of individual human spirits held in bondage by war.

Both poets return to society and more hopeful settings “barred against despair.” For Lewis, the poem “Oxford” describes the psychological space of their homecoming:

We are not wholly brute. To us remains

A clean, sweet city lulled by ancient streams,

A place of visions and of loosening chains,

A refuge of the elect, a tower of dreams.

She was not builded out of common stone

But out of all men’s yearning and all prayer

That she might live, eternally our own,

The Spirit’s stronghold-barred against despair.

Turner ends up finding that psychological space in Olympic National Park:

. . . I put nothing in The Jar of Quiet Thoughts nearby.

Because there is not one thing I might say to the world

which the world does not already know.

Yet both these poets, who have been in harm’s way, have much to say to us.

— Mark Schorr

Parable of Hide and Seek

by Chad Sweeney,

by Chad Sweeney,

Alice James Books, 2010,

88 pages, paper, $15.95,

ISBN: 978-1-882295-82-1

Buy the Book

If you’ve ever had the good fortune to attend a Chad Sweeney reading, then you already know that these events are rapid-fire rehearsals of the word. It’s a different experience, however, when these poems are found on the page, and we are lucky to have a new collection from Sweeney. Parable of Hide and Seek could be described as an inheritor to some of his earlier work in that it builds large, imagistic worlds out of a very keen sense of perception and metaphor. In Parable of Hide and Seek, Sweeney has pared down the language until each poem becomes something of a koan, or a short Gnostic parable.

What I have always admired and appreciated about Sweeney’s poems is their great sense of empathy and emotional maturity. They are never sentimental, but it is clear from the first word to the last that this is someone who pays close attention to the world, to the names and sounds of things, as any good poet should. An example from “The Piano Teacher”:

A music box wound too tightly will explode,

playing its song all at once.

The practice is to unwind the song slowly.

Think of this when you touch the key of C.

In “The Sentence,” Sweeney is at his absurd and imagistic best, insisting:

The bones of Marcel Duchamp

laid end to end

reach all the way

to the bottom of this hill

where a little slab of concrete bridges one

obscurity to another

We go on to discover that the speaker places Duchamp’s jaw in just such a way that “the oblique syntax of bones / repeats its inquiry / in the language of the world.”

This could very easily be written off as an odd ars poetica, but there is more wishing to be expressed underneath this poem. The specificity of naming Marcel Duchamp, for example — the notion that the artist’s bones can be found and re-purposed — gives the sense that all modes of expression are languages that bring us into relationships, and that each strange relationship is a way of speaking to one another on a level of deep engagement.

If absurdity marks the beginning of meaning in these poems, Sweeney’s objective is far from simply causing bewilderment. As he says in the title poem:

I hid as a bullet fired into hay.

I hid as a system of government.

You were my partner in everything.

I lived for you to find me.

This is the genius of Chad Sweeney’s poetry. These poems only mystify so far as to draw you into them, so that the poems become a communion between speaker and reader.

I have personally walked away from a session of reading these poems (and I can’t help coming back to them over and over again) feeling as if I have just witnessed some marvelously catastrophic event. There is terror and pathos in these poems, bullets and governments, but there is also partnership, friendship, and love. In other words, for every complication presented, Sweeney may not give an answer, but hints thoughtfully at a new direction.

— Thom Dawkins

The Giving of Pears

by Abayomi Animashaun,

by Abayomi Animashaun,

Black Lawrence Press, 2010,

82 pages, paper, $14.00,

ISBN: 978-0-9826364-3-5

Buy the Book

The Giving of Pears is an utterly refreshing book of poetry. These delicate and often fanciful pieces are populated by a mélange of ghosts, unborn children, snippets of village life and culture (the author is a Nigerian émigré), and magical tunings. Some of them resemble mystical puzzle boxes, crosses between koans and philosophical conundrums, hearkening back to author Abayomi Animashaun’s study of mathematics. They are clever, sad, amusing and straightforward, without succumbing to pretentiousness. They contain a haunted music and a vigorous imagination, as exemplified here:

I have no words in the machinery of my soul

For how you’ve just pulled me to you.

Released my belt and, now, steadying me

Across the blue flood into the new country.

Divided into six compelling sections, the poems form a colorful travelogue of the psyche, their overriding themes of loss, continuity and hope underscored by an often plain but poignant syntax. In the first section, “Going to School,” Animashaun explores doorways into other worlds, a technique that might quickly become trite; in his hands they have a fresh deftness, as demonstrated in this excerpt from “Tomato”:

Push slowly and enter

A village with its own silent physics.

Its own reddened curvature:

Yellow is the face of the newborn.

Green, the tired hat of the old.

Here sand is red,

And goats lead their shepherd

Through a narrow yard’s edge.

The “Lagos” section acts as hymn, requiem and memoir. The poem “Sunday Mornings at the Barber Shop,” in this section, explores myth, death, superstition and loss through potent imagery entwined with matter-of-fact depictions. This seamless way of braiding the extraordinary with the ordinary is one of Animashaun’s personal hallmarks. Rather than resulting in forced or overly weighted lines, he manages to dance solemnly yet lightly along the edge:

On Sunday mornings

When services begin,

The angels hang their wings,

Abandon their temples,

And come down for a haircut

And nice shave.

“The Unseen” is devoted to ghosts, the unborn, lost loves, and how these beings, whether real or imagined, speak to us, the poetry they engender and the mysterious ways they continue to come and go. “The Other Testament” is an unsettling set of humanistic reinterpretations of religion and figures such as Noah and Mohammed. Animashaun creates an immediacy in these reimagined tales through the use of disjointed phrases, forming a shuffled sense of time in which the present and the ancient become merged. The elegiac musings of “The Tailor and His Strings” form the final section. In “If, In My Next Life,” Animashaun conjures an abstract vision of immortality:

If, in my next life, I have a say

In the molding of clay around

My soul, I’d let my heart be sown

With the sun’s light and traces

From the blue in Cezanne.

Then, geese would find home

In my hands. Birds seeking

Shelter from storms would

Be unafraid to gather and arrange

Twigs on my skull. . . .

The book ends appropriately with an evocation of Rilke, whose imagistic explorations of spirit and time — along with C.P. Cavafy and Kahlil Gibran, and the paintings of Cezanne — guide the poet’s aesthetic journey.

These poems bring to mind Federico Garcia Lorca’s aesthetic of Duende, which often refers to a spirit of evocation, a soulful poetics, an emotional response to music. Christopher Maurer, editor of In Search of Duende, a collection of poems and essays by Lorca, identifies “irrationality, earthiness, a heightened awareness of death, and a dash of the diabolical” as elements crucial to Lorca’s vision of Duende. Such terms also serve to describe Animashaun’s mesmerizing voice.

— Annie Seikonia

Snow Chairs, With A W/hole In One, How The Crimes Happened

Snow Chairs,

by George V. Van Deventer,

Snow Draft Press, 2009,

27 pages, paper, $6.00

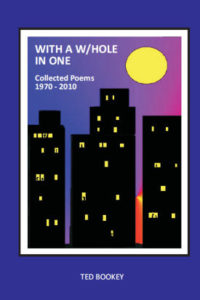

With A W/hole In One: Collected Poems 1970-2010,

With A W/hole In One: Collected Poems 1970-2010,

by Ted Bookey,

Moon Pie Press, 2010,

82 pages, $10.00,

ISBN: 978-1-4507-7

Buy the Book

How The Crimes Happened,

How The Crimes Happened,

by Dawn Potter,

2010, CavanKerry Press,

93 pages, $16.00,

ISBN: 978-1-933880-17-4

Buy the Book

Recently at a state park campground on Long Island, as night came on I heard the different campers who staked down their tents talking around their campfires. Although, for the most part, they spoke English, its shape and form — the vowels and consonants — changed drastically depending on whether I was listening to a Hispanic or Asian family, or a family from New Jersey or New York City. I was struck with the musicality of our language, how the words we use resonate in our mouths, and how that resonance not only reflects our heritage, but also shapes our consciousness of our world.

In rhythm and tone, the three poets whose books I review here are as varied as those campers I heard.

Take George V. Van Deventer, in whose new chapbook, Snow Chairs, he tells of summer nights when “families share each other’s stoop / mixing English and Italian like water to grape.” He writes of how, as a boy growing up in Newark, New Jersey, he danced behind “the organ grinder with his parrot,” how he would hang out “under a lamppost / next to a fire hydrant . . . within shouting distance of home . . . and play kick – the – can, ringalario, drifting through / the freight year.” His language has the earthy immediacy of a street kid who knows that, beneath the rough world, he could survive like a fox, its eyes “blazed wild.” He remembers a fox being killed, the hunter whacking it between the eyes, and it then being reincarnated as a stole that his Sunday school teacher draped over a chair every Sunday. He speaks plainly about his remembrances: “The winter . . . coming / the sky . . . fat and heavy / grey and close in a chilling wind.” I can almost see him by the refracted light of a Coleman lantern, telling his stories to his grandchildren.

If I turn my head, I can also hear the rich, distinct tones of a Brooklyn accent, which fills Ted Bookey’s new book, With a W/hole in One: Collected Poems 1970 – 2010. Listen to someone who delights in words and word play in his poem “Reflections on Hmslf”:

Sufferin’ Reeee – jetionals!

FEEEEEErocious Barars!

Also two moles and of which

One cuts shaving.

The other on the elbow —

Picked at, grows.

& can’t stop smoking enough.

Lucky he’s not a mouse.

His distinct voice — a combination of playful engagement with words and deft shifts in pace and tone, along with his willingness to poke fun at himself and, by extension, many of us who are absorbed with appearances — makes his poems delightful. He has created a wonderful character, Yekoob, who ruminates about the absurdities of world — from Original Sin to loss, aging, and, alas, the falling off of sex. Yekoob is like a camper who enjoys staking up only one side of the tent so the other side flaps. He sets us up to think that he is talking about one thing only to deliver, like a good comic, a contradiction that makes you think twice about what you just heard:

No time left for you to lose

You’d try to find, but knew

How again you’d only gain

One more thing for you

To use again.

But this book is particularly special because it collects Ted’s previous work, all within a lovely cover designed by his wife Ruth. His earlier poems, many about his family, are among my favorites. Textured with his unique blend of angst and humor, these poems charm and challenge us, take the agonies and transform them into hilarities, yet, as they do, never let us forget how much harm and love sleep in the same bed. They clip along at a quick pace, so we have to keep alert to all the shifts and turns. But I could sit by a campfire and listen to them all night. In his poem, “Oral Family History with Heavy Enjambment,” he used the disjunctive quality of enjambment to create his zany family history:

Your father married late in life a women broke his

heart he was young and lost his head I helped him screw it

back we had money how much don’t ask! Easy street we had

a limousine & a maid . . .

A RODENT!!!

fell in a plate of soup and drowned. . . .

Finally, if I turn again, just within earshot of Ted is another voice, one that I must listen to carefully: A woman, who is sitting by her husband (their two young sons not far off, confabulating in their own tent) is speaking. It is the poet Dawn Potter. Her voice has such nuance and range that I fear I am missing any of her precious words. Her new book, How The Crimes Happened, also makes for good campfire reading. It pokes fun — and equally reveres — the rural life in Maine. It encapsulates the exhausting demands of being a mom. It captures the sweet paradoxes of being loved and loving. And, as if sometimes tired of this life, it shifts to Fiends and Goddesses who have it no less easy.

She uses language so carefully and adeptly that listening to her poems makes me feel her reverence for the word. She can sling out beautiful similes, one after another, each building on the previous one, using lovely alliterative riffs like “clinking ice cubes,” and then, with a cavalier shift in tone, toss in a line like: “yes, we did, / even if our attainments were admittedly half – assed and fraught with unexpected chickens / flapping home to roost.”

This tonal shift is always perfectly timed and intentional: It grabs your attention and forces you to see that under the guise of rhetoric, she is actually spinning, slightly under the surface, another tale that finally bubbles to the surface and changes the whole direction of the poem.

She can talk about her son playing in his B – string boy basketball league with what appears to be a cynical edge, describing the spectators as “heavy – set / mother and fathers, parkas unlashed, tired haunches, / roosting on the narrow benches,” as the

“eighth – grade girls cluster in a corner / sucking up Mountain Dew,” as if she is a bystander, separate from them. Then, in the middle of the poem, as her boy’s team is being routed by the opponents, she realized that each parent wants his or her son to do well, and “the very air begins to smell of love — / not just for their own sons, but for every clumsy, familiar / body on the floor, for every boy who ever built Lego racecars.” By the end of the poem, we too are transformed into fans, knowing full – well the boys will lose, but not caring because “they belong to us.”

She can speak as a mother, as a wife, as a lover, as a friend, shifting and changing the tone and shape of her poems to fit the point of view and the subject. In a poem about her hometown, Cornville, she imagines herself as a woman driving along a road, looking at the “for – sale lineup / not of corn but of flat – bellied pumpkins, and her son listening to Joe Castiglione, the voice of the Red Sox, and then manages to weave in Cinderella’s godmother, Grendel, Oedipus, Home Depot, and a Rottweiler, his “head thick as brick,” and bring them together in the final stanza. It is stunning. But she does it again and again. In poems about the Fiend (Satan) and Paradise Lost and in poems about loving her husband, which are both tender and ironic, poems that any of us who have loved someone over decades can fondly identify with, she manages to walk the delicate line between her urge to belong and the inevitability of loss. In the poem “Eclogues,” she turns to her husband, as she notices how “sweat rises from [his] sunburnt neck, salt and sweet,” and then proclaims:

My love. Marry me, I say. You cast

an eye askance and shrug, I did.

She ends the poem musing that

the maples redden,

shrivel, and die.

Nothing needs me,

today, but you,

sweet hand,

cupping the bones

of my skull. Alas,

poor Yorick, picked clean

as an egg.

These are poems that force us to look at the night sky and see in it its majesty, its beauty and its darkness. Our humanity is not a solitary enterprise — she knows it, Ted knows it, and George knows it. They are poets whose voices, although distinct, remind us of the paradoxical, absurd, and yet loving nature of our world.

— Bruce Spang