Violin and Other Questions — (1956)

Selected Poems of Juan Gelman

translated by Hardie St. Martin

Watching People Walk Along

Watching people walk along, put on a suit,

a hat, an expression and a smile,

watching them bent over their plates eating patiently,

work hard, run, suffer, cringe in pain,

all just for a little peace and happiness,

watching people, I say it’s hardly fair

to punish their bones and their hopes

or distort their songs or darken their day,

yes, watching

people weep in the most hidden corners

of the soul and still be able

to laugh and walk with dignity,

watching people, well, watching them

have children and hope and always

believe things will get better

and seeing them fight to stay alive,

I tell them,

it’s beautiful to walk along with you

to discover the source of new things,

to get at the root of happiness,

to bring the future in on our backs, to address

time on familiar terms and know

we’ll end up finding lasting happiness,

I tell them, it’s beautiful, what a great mystery

to live treated like dirt

yet sing and laugh,

how strange!

Keith Flynn

www.keithflynn.net, is the author of five books, including four collections of poetry: The Talking Drum (1991), The Book of Monsters (1994), The Lost Sea (2000), and The Golden Ratio (2007); and a collection of essays, The Rhythm Method, Razzmatazz and Memory: How To Make Your Poetry Swing (2007). From 1987–1998, he was lyricist and lead singer for the rock band The Crystal Zoo. He has been awarded the Sandburg Prize for poetry, the ASCAP Emerging Songwriter Prize, the Paumanok Poetry Award, and was twice named the Gilbert–Chappell Distinguished Poet for North Carolina. He lives in Marshall, N.C., is founder and managing editor of The Asheville Poetry Review, www.ashevillereview.com.

The Spoon River Poetry Review

Letters to the World

— Bruce Guernsey

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me —

— Emily Dickinson

Quick Note about this issue: This Editor’s Issue of The Café Review is different from our normal published reviews. We have asked 14 editors of poetry journals from across the United States two complex question: Why do some poems stand out from others? And what is he state of poetry in America today? Their answers will surprise you. We hope this issue will give poets a better sense of what editors look for in poems. You will get the inside scoop about why different journals accept different types of poems. For teachers, this issue will answer questions students have about the dos and don’ts in submitting poems as well as the perennial question of why poetry matter.

I wish the answer to what makes a poem memorable were as easy as the graph that Robin Williams’ character mockingly uses in The Dead Poets’ Society — one coordinate for importance of subject and the other, mastery of form. Editing would then be a matter of statistics and charting, and not the intuitive cloudiness that it really is.

The Spoon River Poetry Review receives about 3,000 poems a month during our reading period, September 15 through April 15. We also run a very successful contest called “The Editor’s Prize,” which attracts more than 1,400 poems (winnowed to 50 or so finalists). That’s a lot of poetry, and I am blessed to have a very fine staff of first readers who are all excellent poets themselves. But, as editor, I have to make the final decision on the hundreds of poems submitted to the magazine, plus I screen all the work that comes in for the prize. So, what do I look for and what tips the scales one way or another?

Here’s a poem that answers these questions. It’s by Hope Coulter, an Arkansas poet:

The Last Joke

My last trip home before my brother

fell, spiraling down,

out of his green prime

(the orchards in full leaf

the cows wading through thick grass

straining to hear over the sound of their cud

the gears of his truck

the clang of the gate

an oath or two borne their way

on the summer breeze) —

my last trip home before his lungs seized up

with a rare and deadly condition

first identified in veterans of tropical wars,

before his blue amazed eyes flicked toward us

over a hospital gown, his bulky forearms

brown and hard as split wood

resting so strange on a bedsheet —

before the time when his dirt–caked boots

leached by long days of their shine

sat empty beside his guitar,

his cases of worn books,

on the tables his caps, the day’s mail —

before all that, home for a visit,

I got in my car to find

hooked to the fabric over the driver’s seat

a cicada shell, split down the back,

pale, nearly transparent, light brown,

raising its little barbed feet in attempted menace.

Or prayer. Its bulbous dry eye–skins glared

as I plucked it off the upholstery,

and I shook my head, startled into a laugh,

thinking: a brother’s way of saying hello,

trying to get a rise out of me,

even now. Forty–nine, and this is the towel–snap,

the affectionate pop of the rubber band

sailing across the room.

I didn’t know

it would be a last message

before he split his own skin

and vanished

into whatever sort of rise

might be granted, not to be seen again

but only heard, heard in the roaring absence

that towers over our heads, like a chorus

unseen, stacked in the trees day and night, that twangs

like a giant rubber–band choir, a choir of curses

borne on the breeze.

He didn’t know

when he stuck it beside the visor (cracked carapace,

buggy salute) where he was going,

what he was finding out soon.

“The Editor’s Prize” is stiff competition, and not only in those staggering numbers but in quality. So, what led me to include Coulter’s as one of the finalists I sent on to the 2007 judge, Ohio poet Philip Brady?

Here’s a hint: Instead of scanning her poem onto the page just now, or duplicating it in some other technological way, I typed it. Indeed, had it been acceptable, I would have written the poem out by hand because The Last Joke has that kind of feel for me — that it was handwritten. It’s precisely that kind of poem I look for: one that is really “a letter to the world.”

So much of what I read as an editor seems hurried, computer–driven, written for the purpose of publication and the enhancement the poet’s “career” — the poem as exercise, based on some obscure quotation or reference to an esoteric source, perhaps a painting or musical composition. Certainly, great poetry has come from such sources, but when I read dozens and dozens of poems with the same kind of allusive genesis, I suspect that I’m really reading assignments from a master of fine arts class.

There is none of that in Coulter’s poem. Instead, there’s an urgency at its source that has led the poet from silence into sound. And I’m not talking about “sincerity” here — some of the worst poems ever written were the most sincere. A cry or a wail is sincere, but neither of these is poetry. What lifts The Last Joke from mere moan into powerful verse is its wonderful ordering of sound and sense which are both in service to what Robert Frost called “the lump in the throat” that generated the poem to begin with.

I also look at how a poem appears on the page. When I see no white space, I confess to being cautious because silence is as much a part of a poem as is sound. The poem that floods the page with verbiage suggests to me that the poet has not paid much attention to shaping. And I listen as I look, wanting to hear lines, not sentences disguised as such. Is there a rhythmic pattern at work here, or are the line breaks determined primarily by dependent clauses or prepositional phrases — that is, by syntactical units instead of sound?

When you go back to Coulter’s poem, you will hear a powerful pattern based on anaphora as the poem proceeds at the same time with necessary exposition and exacting imagery. Her metaphoric use of the cicada is both brilliant and heartbreaking, but metaphor is something I find sadly lacking in so much of the poetry I read. A poem is burdened by adjectives not enhanced by them, and all too often I find the literal description trying to do what a figure of speech can do far more succinctly and, thus, more memorably.

We seldom get personal letters anymore, ones with actual handwriting, both inside and on the envelope. When we do, those kind of “letters to the world” stand out in the mailbox — and on the page.

Simpatico Poets Press

The Active Voice

— Daniel Kerwick

Quick Note about this issue: This Editor’s Issue of The Café Review is different from our normal published reviews. We have asked 14 editors of poetry journals from across the United States two complex question: Why do some poems stand out from others? And what is he state of poetry in America today? Their answers will surprise you. We hope this issue will give poets a better sense of what editors look for in poems. You will get the inside scoop about why different journals accept different types of poems. For teachers, this issue will answer questions students have about the dos and don’ts in submitting poems as well as the perennial question of why poetry matter.

In the aftermath of what we, in New Orleans, refer to as “The Thing” (Hurricane Katrina) the notion of “being there” took on a new focus. Surreal to be sure, an altered landscape emerged that we saw with cautious eyes, an etched clarity, and perhaps somewhat optimistically simply because we had survived. But, too, it haunted us with a lingering fear that the intangible uniqueness of our city might be lost forever.

One of the positive things to come out of the disaster was that local artists, especially poets, stepped up to the plate to put these fears to rest. It was out of the many poetry readings during that time that Simpatico Poets Press was formed. Born out of necessity — not to go crazy in our fragile, altered world — Simpatico evolved from raw pamphlets and chapbooks passed among friends to now, three years later, what is known in the trade as “book art” publications that were even recently displayed in a gallery show of such work.

To date, Simpatico Press has published more than 20 titles by New Orleans poets who are active on the local scene. The books are all handmade and hand stitched at Simpatico Studio, with press runs of 50 or 100 copies. We enlist local artists to contribute images and interns from local schools have even helped out. The books are sold at readings, book fairs, and a couple of local bookstores. When I travel, I always bring along a few copies of my own work to trade with other poets.

The poets that we’ve published have produced true documents of the time and voice of our region. Listen to the range of their voices:

To begin a tale that decides its own meander…

— Megan Burns

We pick the ripest harbingers of light . . .

— Gina Ferrara

One should have gentle addictions

a sense of the maladjusted . . .

— Thaddeus Conti

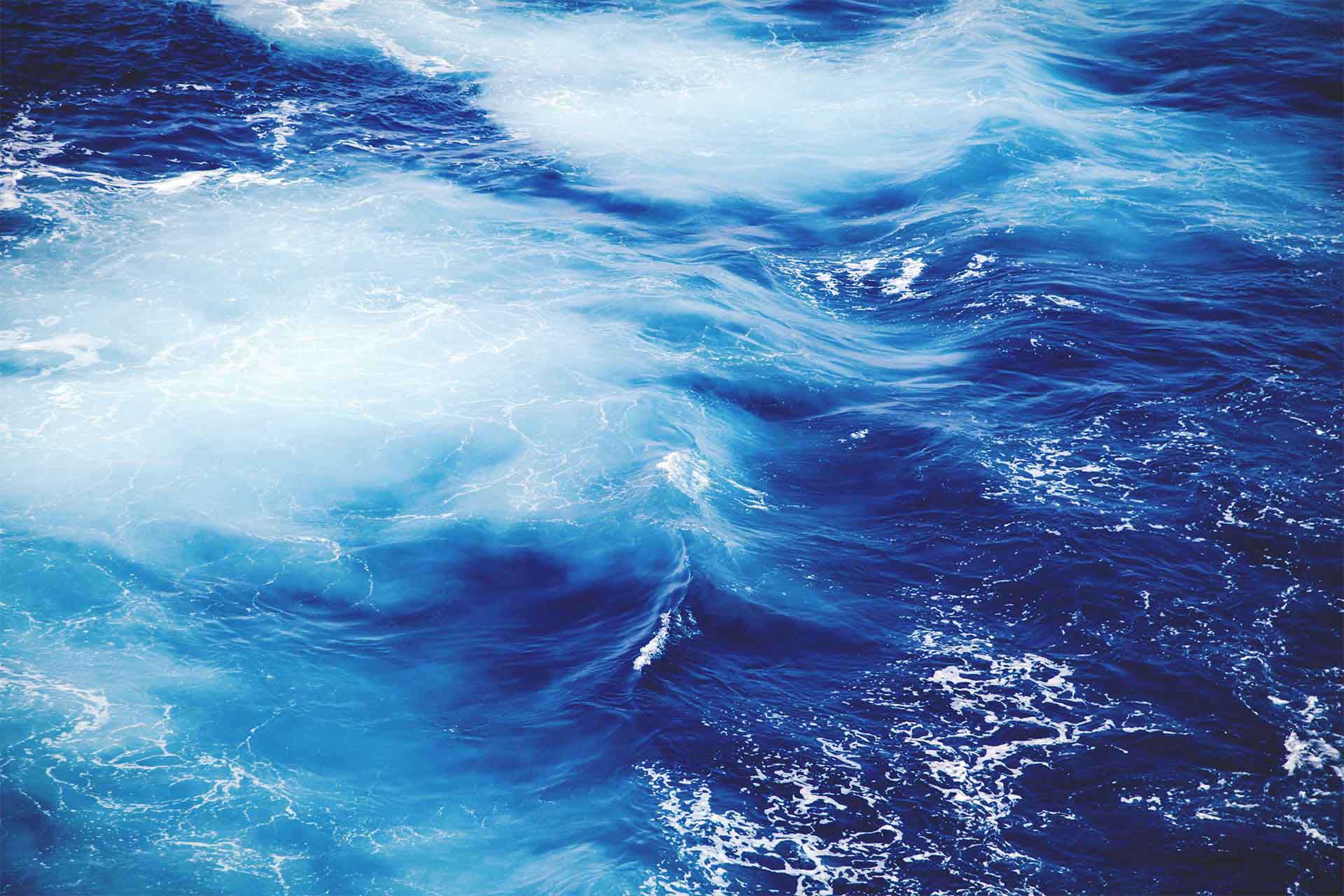

These were opening lines that made me want to hear more, dive deeper into the poems, swim in their language. The absence of the declarative “I” dotting the poems like billboards of self allow the reader to use his or her imagination, to participate in its movement. Meander where? What harbingers of light? Why a sense of the maladjusted?

A friend of mine, when using “I” in a poem, has a rule that it can’t appear until the eighth line. But, of course, rules are made to be broken. As an editor, I usually pass on “poems as diary,” poems that lack persona or an inherent love for the musicality of language. “Opinion poems,” as I call them, are better off buried in essays or bar chatter. I can tell you why the New Orleans Saints lost last Sunday or how our government dropped the ball after Katrina. But in a poem? Didactic political statements usually kill a poem that, in itself, is political.

An example of avoiding this is seen in New Orleans poet Megan Burns’ poem At 30. Burns is able to move from abstractions like the vagaries of memory and desire into the use of allegory in order to illustrate her concerns:

. . . a slumbering city

slips beneath the water but still no metaphor

that I could hand you

that would help me

tell you

how

that

feels . . .

In her poem, fact and imagery fit into a dream landscape as context without a linear narrative other than “the poem,” which ends with an island of ferocious outcomes.

After hearing Burns read, I wanted to see more of her work and experience it on the page. What I look for in poems is a cadence that moves and surprises me, a return to the form of the poem that once again departs, pulls me into a landscape that is as unfamiliar as it is familiar. I look for the sense that the poet’s work is part of a whole without being redundant, that, if one shed the poems’ titles, we’d have a decent, serial work.

Like New Orleans musicians, who wear many hats and play music of numerous genres and styles, a poet who is not afraid to take risks, play with different forms all in the same piece, will sometimes find far more interesting results than adhering to shopworn formulas.

Born out of local readings, Simpatico Poets Press seeks to capture raw energy on the page. But the design of a proposed book can inform the choices an editor makes about a particular poem. The rejection of a poem does not always mean that the poem is not successful, or that there is not something valuable in the effort. In most cases, it is apparent that a writer is a skilled poet, who is not only busy sharing his or her work with others but is interested in hearing other voices. Poems are rejected for many reasons, some of which are based on craft, others based on how they fit into a particular book.

A question I like to ask young poets is, “Who are you reading lately?” Some stammer and say something like, “I only like Bukowski.” Nothing against Charles Bukowski, but my red flag goes up if they read only one poet, and that’s when I suggest they take a trip to a bookstore or library.

A journal or book can be a good chronicle of the times and all the voices embraced that precede it. Besides the meditative benefits, and the need to say something, one of the great benefits of poetry is people simply gathering and sharing. Poems are meant to be read aloud; books facilitate that act and are a great talisman to take home, to pull out now and again to howl with.

Here, I like to share a poem by New Orleans poet Thaddeus Conti:

The Sexual Prowess of a Meteorologist as Held over

from the Age of Aquarius

one should have gentle addictions

a sense of the maladjusted

so as when those around them step out of the norm

they can reign them in as well as earn a sense of shame

sometimes it is so easy

to be under the scalpel

in a world of sores

if I were a musician I would suspend theory

and call on

the absence of

a certain knowledge

to write our song

When reading this off the page, I can hear Conti’s voice and am pulled into a mysteriously shared space where all of us are under the scalpel. With his use of humor and pathos, there is movement in this poem away from the facts and anguish over the predicament, here, in New Orleans that reveals Conti’s quirky, singular voice honed at gatherings where the business of poetry is in its rightful place.