Translations from Bark Beetle

by Jody Gladding,

by Jody Gladding,

Milkweed Editions, 2014,

96 pages, paper, $12.40,

ISBN 978-1-57131-455-0

Buy the Book

We like to write on things. It’s what we do. Mostly on paper, but . . . I once got in a bit of trouble in college when I got a little carried away while chalking the campus quad for a student activist group. Maybe it was my inner Jody Gladding coming out. Whatever it was, I now regret my callow chalk self, but in that dusty moment of chalking, there was such a rush to write upon the unexpected. I think Jody Gladding knows what I’m talking about.

The poems in Translations from Bark Beetle are playful, limited and desperate. Let me explain.

In the book’s second poem, “Spending Most of Their Time in Galleries, Adults Come into the Open on Warm Sunny Days: Translation from Bark Beetle,” Gladding says, “•’ve learned through wood / yo• can only travel in one direction.” The dots are explained as translation challenges, but I just ignored them and read on, and with Gladding as guide, I too learned through wood, and stone, ice (melted), tea bags, fear (!), and liver scans, among many other things (photos in the back of the book).

I couldn’t help but feel how fun this all was, especially when I read the poem written on the icicle, which, by the time it was photographed, had melted. Gladding’s poetry is a radical mark making. These hark back to the declaratory act of chalking a sidewalk, such a physically satisfying medium, the concrete page, and then the poems transform the pedestrian into the poetic, surpassing my petty college act and moving into the realm of art. What Gladding is doing is devilishly fun, and more than a little subversive.

Such an experiment also feels necessarily limited. We place confines around us to give us structure with the hope that within restriction we find freedom, and thus surpass our limitations. This doesn’t always happen for me in reading these poems. When one is writing a poem on /in a change-of-address form, there’s literally only so much space to move around (pun intended). Sometimes these experiments feel epigrammatic and easy to dismiss. And yet, sometimes these limitations allow for true flights of beauty well beyond the physical. “Swallow,” written on a tongue depressor, is one of these:

swallow

the words

he said

we

don’t

want

them

all over

the map

of

your

tongue

and if

they

burn

the roof

of

your

mouth

we don’t

want

them

jumping

to

safety

That poem crackles. It’s fast and dangerous. “Seal Rock,” written “on split slate,” is another such poem that takes a halved stone to create one of the most beautifully sparse and lovely marriage poems I’ve ever read.

I most feel these poems are an act of desperation. It’s something I continually felt as I read the book. From “roc”: “but what if / the invisible is / simply / the unseen.” One can’t ignore that this poem was written on a feather, both a flimsy relic of flight and the archaic instrument of poetry. Gladding, in these poems, wants to bring the invisible onto the visible, to make tangible the ethereal. How could this be anything else but a desperate attempt to make sense of a cruel, dumb world? Poetry as insurance against overwhelm. What else has poetry ever been in the history of the word? What can poetry do when “we [drive] our inflated cars to our box stores and [fill] our giant shopping carts”? Jody Gladding takes our collective desperation — and my chalky regret — makes it hers, and gives it substance.

— Jefferson Navicky

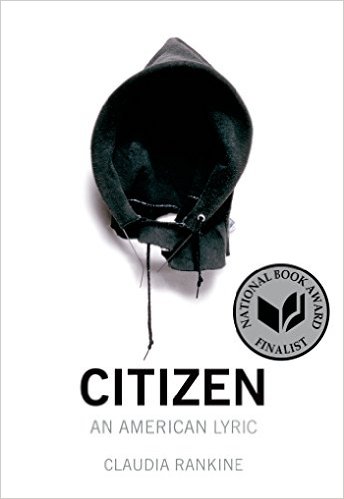

Citizen: An American Lyric

by Claudia Rankine,

by Claudia Rankine,

Graywolf Press, 2014,

169 pages, paper,

ISBN: 978-1-55597-690-3

Buy the Book

It is the late 1970s. Our family has recently moved to a four-bedroom home amidst the tree-lined community of Palmer Woods on the outskirts of Detroit, where doctors, lawyers, and college professors of color have resided for many decades. My father, a college instructor and real estate broker, uncharacteristically wearing blue jeans and a sweatshirt, is seated on a bench facing the backyard gardens, smoking a pipe. Three middle-aged white men, who work for the company he has hired to repair the leaky lawn sprinkler system we inherited, are surveying the landscape. After they have made their assessments, one of the men walks up to my father, clears his throat and asks: “Could you find Mr. Donaldson and tell him we’re ready to give him our estimate?”

This is the kind of racially-charged verbal slight that Claudia Rankine, who was born in Jamaica, an island of varied nationalities, explores in her recent poetry /prose collection, Citizen: An American Lyric. The book is the first to be nominated for two categories for the National Book Critics Circle Award, poetry and criticism. Rankine’s literary style is indeed diverse and boundless, weaving poetry, essay, dialogue, visuals, as she creatively documents the psychic damage to people of color caused by daily life insults, unconscious or intentional, uttered by white people. Through her words, we learn how words, spoken in the classroom, in the supermarket, on television and the radio, and in corporate settings, define a person from outside the color of their skin.

“Poetry allows us into the realm of feeling and it’s one place where you can say, ‘I feel bad,’” says Rankine, who is the author of four previous books, chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and a professor at Pomona College. She elaborates:

Certain moments send adrenaline to the heart, dry out the

tongue. . . . Haven’t you said this to a close friend who early in

your friendship would call you by the name of her black

housekeeper? You assume you two were the only black people

in her life. Eventually she stopped doing this but she never

acknowledges this slippage. And you never called her on it

(why not?) and yet you don’t forget. . . . Do you feel hurt

because it’s the “all black people look the same” moment, or

because you are being confused with another after being so

close to the other?

Rankine’s writing about such painfully visceral situations is often beautifully fluid. Though primarily focused on racism against African-Americans, it is possible for, say, women, gays, the disabled and the aged to visualize themselves in similar scenarios. “These tales of everyday life . . . expose what is really there: a racism so guarded and carefully masked to make it all the more insidious,” wrote poetry scholar Marjorie Perloff of Citizen. Rankine describes ominously ordinary moments in her academic’s life:

You are in the dark, in the car watching the black tarred street

being swallowed by speed; he tells you his dean is making him

hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out

there. . . .

Sitting there staring at the closed garage door you are

reminded that a friend once told you there exists the medical

term John Henryism — for people exposed to stresses

stemming from racism. They achieve themselves to death

trying to dodge the buildup of erasure. . . . You hope by

sitting in silence you are bucking the trend.

This poem in its entirety takes us well beyond a simple awkward moment. These are experiences unique to black people and occur largely because of their skin color. It tells us that a racial divide persists in American culture regardless of how close relationships may be. Rankine also alludes to the psychological confusion and frustration created in the minds of the recipients by these seemingly thoughtless words and actions. She speaks of the accumulative stresses that bear on a person’s ability to speak out, perform, and maintain emotional health.

The media does their ample share of perpetrating color divisiveness. The acute insensitivity and obliviousness of many whites is illustrated in her essay about tennis players Serena Williams and the late Arthur Ashe, when sports commentators praised Williams for “growing up” and Ashe for being “dignified and courageous,” when they rose above the blatantly racist onslaughts they had encountered. The implication is that being angry about racism is somehow immature and ungracious, and that the best way to confront injustice is to do so without emotion, and certainly without making a scene that embarrasses white people.

The title Citizen: An American Lyric is not accidental. “Our addressability is tied to the state of belonging, as are our assumptions and expectations of citizenship,” Rankine argues. Her book is a muscular confirmation of the effects of racism on both the individual and our collective society in a so-called post-racial country, and yet it still exudes optimism for a better world. The cover itself, a 1993 piece of artwork by David Hammons, depicts a hooded sweatshirt reminiscent of the “hoodies” that became an iconic protest symbol of the Trayvon Martin killing. A black and white photograph of a suburban sub-division with the street sign “Jim Crow Road,” taken by Michael David Murphy, speaks volumes.

Though making sense of racism is not the goal of this collection, it does give us warnings signs about the danger of merely accepting racism as a given in American culture, to the extent of passively doing nothing to change destructive mindsets. “If that rude shopper finds himself in a position of power — i.e. on a jury, organizing Katrina evacuations, or if you arm that fear and call it policing — then you’re going to get these explosive events,” Rankine asserted in a recent PRI radio interview.

Her book of meditations on racially charged encounters reminds us of countless current events, including when politicians and other public figures have made outrageously offensive statements about people of color and, instead of acknowledging the tragic

history, as well as their own culpability behind their affronts, they

either dismiss the action or merely apologize for upsetting a perceived over-sensitive, politically-correct group of individuals who can’t take a joke.

When my father was confronted by the lawn sprinkler man, he turned and walked into the house, then later returned dressed more formally to go to his real estate office. “I understand you’re looking for Mr. Donaldson. I’m Mr. Donaldson,” he said. The expressions on those three faces made a perfect tableau of a wake-up call. Because of my father’s forbearance and sense of humor, those men would continue to work for him over the years. Together, they bridged an ethnic chasm. Citizen: An American Lyric is a collection of extraordinary social commentary that helps us see our lives more clearly through the suffering we both inflict and allow, thereby making it possible to see a path toward reform.

— Leigh Donaldson

Gabriel: A Poem

by Edward Hirsch,

by Edward Hirsch,

Knopf Doubleday, 2014,

96 pp, hardcover and paperback,

ISBN: 978-0-385-35373-1 (hardcover) and 978-0-8041-7287-5 (paperback)

Buy the Book

Poetry has replaced religion for me as a sustaining force in my life. Often when I go to the Grolier Poetry Book Shop on a Friday night, there are flashbacks to the Chicago synagogue that sustained me through my eighteenth year. Poets like Marge Piercy and Ed Hirsch — not the synagogue or the Bible — are now the places that I go for spiritual refreshment. Thanks to poets like the aforementioned and my focus on poetry, I have come to believe that there are high tides and low ebbs in every spiritual tradition. All should be respected, and none should be taken for granted.

Gabriel: A Poem, by Edward Hirsch, has taught me more about the unconditional love a parent must always have for a child than I thought I had learned while teaching and raising children. Full disclosure: I graduated from the same small college as Ed, who is about ten years younger, so he has always been in my rear view mirror. We’ve had many good conversations. I’ve known about his son Gabriel’s unconventional life and the diagnosis of Tourette’s that never quite fit the actual case.

Since hearing a few vague details of Gabriel’s death, I had not been able to fathom the pain that Ed must have been going through — that is, until I read his masterful poem. The poem is so powerful that I can write to Ed again, and say, I think I understand. Even though you have a broken heart, you are a fine father. You will never stop caring for the world’s children and writing poems that care for them. I can say that his poem is completely accessible to any parent who has reached, with a child, impasses that can be overcome with unconditional love.

While Gabriel was very much alive and full of promise, Hirsch wrote a chapter on elegies, “Three Initiations,” that appears in his now classic How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry (1999). Much of this chapter gives clues to how to approach Gabriel: A Poem, Hirsch’s own heart-rending elegy. So I use Hirsch’s own words to guide me through.

In the book-length poem, Hirsch mourns and looks for solace in

the act of writing. He does, he says, “what Freud calls the work of mourning, ritualizing grief and thereby making it more bearable. . . . ” He “turns loss into remembrance”:

I peered down into his face

And for a moment I was taken aback

Because it was not Gabriel

It was just some poor kid

Whose face looked like a room

That had been vacated.

Again, I turn Hirsch’s own words, from How to Read a Poem, to what I hope has happened for him in Gabriel: “The elegy opens up a space for retrospect (‘I see now’), for overwhelming personal feeling, and it drives a wordless anguish toward verbal articulation.” Again the parent at his child’s bedside, Hirsch gains that tender view:

But then I looked more intently

At his heavy eyelids

And fine features

The elegy also “establishes a precise relationship” between Hirsch and his beloved son. Hirsch reaches the point he describes by immersing himself in the poetry of grief. In this process, he passes through a white-hot intensity, out of which comes utter honestly about his loss, which finally brings him to — for this reader, and fervently I hope for my friend — a true “richness of feeling” for his departed son.

He had always been a restive sleeper

Now he was weirdly still

My reckless boy

By praising Gabriel as “My reckless boy,” Hirsch also names the most recent of his son’s dysfunctions and arrives at some sort of understanding.

Another clue of how Hirsch feels for his son comes in his glimpse back to the Humanities class in which a young Grinnell teacher named Carol Parssinen led him to discover the healing power of The Iliad. Homer’s epic “opened up a space in me that made it possible to name what I would feel. . . . ” His descriptions of Gabriel are infused with much of that power:

Dressed up for a special occasion

He liked that navy-blue suit

And preened over himself in the mirror

Hey college boy the guy called out

On the street in Northampton

You look sharp in those new duds

Hirsch says that he loved how “unflinching” Homer was: “I recognized [the Iliad’s] demonic power, its outsize emotion and epic grief. I was wounded by its truth. And I was also healed by it.” Finally, we can only hope that what Hirsch learned about that ancient poet’s poetry — “I was also healed by it” — is also true today about his own words to Gabriel.

— Mark Schorr

No Girls No Telephones

Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton,

Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton,

Black Lawrence Press, 2014,

28 pages, paper, $8.95,

ISBN: 978-1-62557-999-7

Buy this Book

Probably the finest essay on poetry I’ve read this year is Matthew Buckley Smith’s “Why Poems Don’t Make Sense,” which can be found here in 32 poems. In it, he explains what sense is, how it differs from logic, and what nonsense entails, while illuminating the concept of theory of mind in relation to poetry. It’s a smart, accessible, and important piece.

I start there because at the time I first read Smith’s essay, I was also in the midst of reading No Girls No Telephones by Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton. A collaborative chapbook of paired poems that take their shared titles from lines of Berryman, NGNT comes with an author’s note at the end that I’ll reproduce here in part, as it’s necessary for understanding how I’m coming at this review:

Authors’ Note:

Brittany had the idea of writing an opposite imitation of a

John Berryman Dream Song, and suggested that Rebecca write

an opposite of that opposite. It was a strange game of literary

translation.

Simone Muench blurbs on the cover that the poems operate as a game of telephone to filter the sense of poems by John Berryman through Cavallaro and Hazelton. The authors’ note explains the process whereby noise was added to the system, so to speak, with opposites of opposites reflecting off one another to introduce distortion. As you might expect, just like in a game of telephone, the message at times becomes garbled well beyond lyricism, crossing into true nonsense. I tried all the usual ways of maximizing the poems’ content: reading aloud to myself, reading to someone else, reading out of order. Nothing worked. And yes, there’s a natural pleasure born of unexpected and unexpectable constructions, but I kept thinking about Smith’s essay and my native distaste for nonsense.

So, brief aside, what’s wrong with nonsense? To me, it smacks of a writer who, though having nothing to say, nevertheless seeks an audience. And was that what was happening in NGNT? No, but I was having a hard time figuring out what was happening. While I’m only marginally familiar with Cavallaro, Hazelton’s poems are not merely sensible but frequently profound. The meaning had to be in there somewhere. Berryman may be ethereal or even transcendental but he isn’t nonsensical, and the best games of telephone retain echoes of the intended message despite the accidents of flawed transmission.

Then, once I saw it, how had I not seen it? There aren’t just structural parallels between the paired poems; they are like transparencies to be laid one over the other. I suspect my initial blindness to this came from holding too tightly to the game of telephone concept. I kept trying to understand it through that lens, however figurative, despite my deepening frustration. While I can certainly see how it was relevant to the composition of the book, it put me on false footing to assume this would be the most fruitful way to read the poems.

This misstep was admittedly my own fault. That the method of composition does not imply the method of interpretation may be self-evident to others, but this was a learning moment for me. Anyway, what was genuinely captivating about the book was how two strophes of nonsense, on opposing pages, would give rise to something sensible if non-concrete, “sense without reference,” when considered simultaneously, and that this sensibility resonated as authentically Berrymanesque. It’s not the intuitive way to read poems, and it’s not exactly easy, but it taught me something. Not in the way of aphorism or analogy, or any of the pleasant methods through which I expect to encounter a lesson in most poems, but by frustrating my understanding and then composing sense in a manner I had never before experienced.

The last thing I want to get into is how Cavallaro and Hazelton play with opposites throughout NGNT. I’m fascinated by opposites, not so much in the antonymic dark / light, land / sea kinds of couplings, but when we think, for example, of the opposite of a park. The first thing that comes to my mind is wasteland, but what about office the opposite of park? This way of thinking can work as a lever for the imagination. For instance, what if the opposite of plant is not animal, but something that thrives on moonlight and vodka? The opening lines of the poems “Mission Accomplished” demonstrate this effect to highlight a mode of seeing and thinking that is acutely poetic:

Her inner life was left on a marked tree

And its opposite:

Our outer hearts are found in an unmarked grave

That’s just for the flavor of what’s happening. Overall, my experience of reading NGNT was non-recreational but rewarding. I don’t know that it’s exactly avant-garde, but for me it expanded the possibilities of nonsense in ways far more sophisticated than the attempts made in the vast bulk of conceptual poetry I’ve come across. And it has me thinking I perhaps ought to mail my copy to Mr. Smith.

— Andrew Purcell