Our Andromeda

by Brenda Shaughnessy.

by Brenda Shaughnessy.

Copper Canyon Press, 2012,

$16, paper,

ISBN: 978-1-55659-410-6.

Buy the Book

We do artists few favors when we say, as a means of praise, that a work “hits home” — that some subject matter or other (oh subjectivity!) struck our sympathetic frequencies.

The ex-baseball player (for instance) whose favorite film is Field of Dreams, or the speedboat-owners toasting with Coronas before a Jimmy Buffett concert — how much do you trust their assessment of Kevin Costner’s emotional range or the lyrical depth of “A Pirate Looks at 40 ?”

They’ve seen a version of themselves, and they like what they see. And yet here I am under the spell of some poetic Propinquity Effect myself, wanting to tell you about weeping while I read Brenda Shaughnessy’s Our Andromeda aloud to my newborn daughter, as if a few tears might recommend a book.

How can you reconcile catastrophe and gratitude; burdens and blessings; terror and joy ? These are the concerns that sweat at the edges and burn at the heart of almost every poem in Our Andromeda.

Shaughnessy, whose son Cal suffered a brain injury during childbirth, uses Andromeda (both the book of her own making and the distant galaxy to which it refers) as a world of parallel projections. This is a world, as she wrote in a Poets & Writers essay, “in which my son was not injured at birth, a world in which he’d been allowed to live in his own body without the pain and restriction of cerebral palsy.”

A fantasy. A double-life. A different life, as she states in the title poem (which takes up roughly a fifth of the collection):

Wait till you see the doctors in Andromeda,

Cal. Yes, the doctors. It’s not the afterlife,

after all, but a different life.

The doctors are whole-organism empaths,

a little like Troi on The Next Generation

but with gifts in all areas of the sensate self.

Yes, 2012 seems to have been the year of refreshing sci-fi references in popular poetry. Tracy K. Smith’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Life on Mars got its lift from the space-stuff of Ziggy Stardust, Stanley Kubrick, and Edwin Hubble — searching the inner and outer dimensions for a mutable soul.

And in Shaughnessy’s Our Andromeda, where the fragile delivery of her son is described in terms of intergalactic travel, we get lines like this:

You came from Andromeda, Cal,

that other galaxy. Came to me, to us,

the moment you were born,

when the membrane between

worlds snapped and all that alien love

flooded my body. It came from you.

In her second collection, Human Dark with Sugar, Shaughnessy mixed the mythic with punk rock vim to decode moments of romantic longing. This time around, her desire is not zeroed-in on one specific absence, but aimed like buckshot at every future that would refuse her or her family, as in “Liquid Flesh”:

He howls with such fury and clarity

I must believe him.

No god has the power

to make me believe anything,

yet I happen to know

this baby knows a way out.

This dark hole closing in on me

all around: he’ll show me

how to get through

the shock and the godlessness

and the rictus of crushed flesh,

into the rest of my life.

And there is the hope, the stubborn motion forward. Shaughnessy is able to portray Cal not simply as an anchor for the book, but as the life at the center of her life, as the star feverishly pulsing in two galaxies at once:

Galaxies exploding everywhere

around us, exploding in us,

Cal, faster than the lightest light,

so much faster than love,

and our Andromeda, that dream,

I can feel it living in us like we

are its home. Like it remembers us

from its own childhood.

While the poet herself is suspicious of the intersection of “truth” and artifice (“Heart, what art you ?”she writes in “Artless”), I’m never far from feeling the off-the-page reality of these poems, in the most confessional of senses.

But why the tears ? Well, my girlfriend and I and our daughter had just gone through a highly traumatic birth experience, spent a couple weeks in the hospital, and come home to make our big adjustments. When I checked the mailbox on that first day back, Our Andromeda was waiting to be opened. All in one afternoon we read it to our daughter, and I cried, and cried, and cried.

Of course it would be crass as a reader and as a new father to say Our Andromeda “hits home.” My daughter recovered; Cal’s debilitation is permanent. And I hope that in making such contrasts and comparisons I’m not further condescending to Shaughnessy’s “sad new family struggling to find / blessings where blessings were.”

It’s just that in reading Our Andromeda, Brenda Shaughnessy’s defiant faith in love, all the more compelling for being hard-won, helped me better understand what it means to be a parent. Her poems help us see more clearly the ways in which love, if not the body, can be regenerative.

And “. . . if all possible / pain was only the grief of truth,” as Shaughnessy supposes in “All Possible Pain,” then solace must be possible in spite of that truth.

Or as she says in “Miracles:”

A light. Sailing a signal

flare behind me for another to find.

A scratch on the page

is a supernatural act, one twisting

fire out of water, blood out of stone.

We can read us. We are not alone.

Shaughnessy is the kind of poet for whom writing is not an act of mere relating, but of relation.

— Christopher Robley

Then Go On

by Mary Burger.

by Mary Burger.

Litmus Press, 2012,

93 pages, paper,

ISBN: 978-1-933959-14-6.

Buy the Book

When I read the poems in Mary Burger’s Then Go On, I have the feeling of floating up along the ceiling, up near the maple-leaf molding, up where the day’s heat collects. From this elevated, even light-headed, position, I observe the world of my parlors, and I find the surprisingly precise ability (I am, after all, hovering fourteen feet in the air, and I do not usually find myself at such a perspective — I am not such a light person!) to point with confidence and name exactly what I see. This experience is like a version of “I Spy”: “I spy with my little eye. . . . ” What I spot is not limited to the child-like — a fire truck, a tiger, two little

mice — but also includes floating abstractions: accepted premises, optimism, futurity, arbitrariness, and synesthesia. This is indeed a heady game, not only for the range of pointed-at things, but more so for the confidence Burger inspires in my otherwise rather doubtful pointing. After all, as a reader, I am not all that confident in my ability to identify “synesthesia of attachment,” for example, but with these poems, I find myself an “I Spy” master. I’m hitting everything: Social Identities, Energy, Light, Chairs and Plastic Farm Animals.

Burger’s book is perhaps most poignant when its author, so comfortable in helping readers hit new philosophical ground, really grounds us in her reality. Poems like “Fire Cat” do that easily, bringing the reader through the phonetic poem of a seven year old:

A small hole appears in the middle, a dot of white in the

moving

image, and spreads toward the edges of the frame, orange and

black and white

and blistering, eating the shapes around it, hungry

microphage,

until it eclipses even itself and there is only

white, light, unimpeded, unfilmed, unfiltered. . . .

i like tuu bee a fier cat.

I too like when Burger is a fire cat. Her crackling language can roar back words telescopically through space and time to aid this reader in hearing the constant soft-sound drone of Interstate 70 that passes far from, but near, my parents’ house in Southeast Ohio. From “Energy, Light”:

The background roar of the distant highway, that some might

hear as an explanation of origin, that some might regard like

the microwaves that permeate the universe, evidence of the

beginning, of the beginning of the real. . . .

I felt grateful that Burger so quickly took me back to this sound memory.

Later, she’s downright funny in the poem “Snoring is Waking,” in which the narrator butters toast at 3 am, blithely battles with her bed partner, Snoring, who does not suffer the narrator’s insomnia. It’s this tension between the ignorant bliss of Snoring and the narrator’s wakeful amazement at Snoring’s ability to sleep that gives the piece its spark. Anyone who has laid awake at night staring incredulous and jealous at a partner’s supine slumber will especially appreciate.

The other piece that stuck out to me was the commiseratingly conspiratorial “All New Yorker Stories.” As broad as the title may at first appear, Burger’s analysis rings startlingly true. The piece deconstructs two actual New Yorker stories, one from Mary Karr and one from J. Robert Lennon. It’s humorous — see reference to Kevin Spacey’s character in American Beauty — but after reading the piece, it left me mightily impressed by Burger’s analytic ability as a far-from-the-mainstream artist to so brazenly and insightfully lay bare the establishment.

This returns me to “I Spy,” and my happy, languid, peaceful floating along my parlor ceiling. I want to take this confident pointing from the pages of Then Go On out into the outside world. After all, I could use — and who couldn’t ? — a little extra brazenness against the establishment. The book is a pocket guide for such insurgences of sight.

— Jefferson Navicky

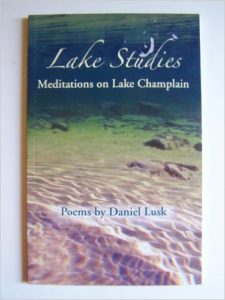

Lake Studies: Meditations on Lake Champlain

by Daniel Lusk.

by Daniel Lusk.

Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, 2011,

96 pages, softcover, $14.95,

ISBN: 978-0-9641856-8-5.

Buy the Book

From the preface of Daniel Lusk’s Lake Studies, we learn that its poems are the result of “two years of research, of the underwater character and human and natural history of Lake Champlain.” For some of us, this carries the enticement of works bathed in natural history, sprinkled with science. Not quite. These are “works of imagination,” not to be confused with “history, archaeology, journalism or other science.” They’re poems. And yet, how do two years of research into a big lake manifest as poetry?

By going under. There, Lusk has us peer into darkness and hear sounds muffled. There is less clarity and more mystery; all is otherworldly. But before the poems actually dive, we wet our feet at or above the surface. There, Lusk often draws our attention to sound, as in “Story”: “Whisht! Listen.” In this case, the soundscape is an ancient one of thunderous, shrugging glaciers. Whispers, voices and cries, populate another early piece, “People,” and in a sequence of poems about nautical disasters, the sounds at the surface are wild and cacophonous, mostly human, soon stifled forever.

Lusk gives us bearings before the dive. A map is a logical tool for this, and a graceful 18th century one accompanies “Drowned Lands,” our first bird’s-eye view of the “winding, riverine road” along the southern half of the lake (the only map or aerial photo in this collection of images and text, regrettably). We encounter familiar animals — egrets, mallards, otter, and mink. Here, as elsewhere, though, Lusk inventories so much in the way of species or cargo that he often distracts from the narrative.

The lake setting established, Lusk takes us down with the piece “Nocturne”: “When we go below, / we almost expect to see the stars / . . . fixed in their places along the bottom.” The poet applies philosophical ideas with a deft and wry touch, as in “Salon Noir,” in which he re-imagines the light and shadows from Plato’s Allegory submerged. In “Lake Apparition,” he merges monster, silence, and shadow: “The lake, like our dreaming selves / redolent of secrets / wondrous and perilous.” His descriptions of fish (sculpin — “Full-lipped / as tulips in their turbans”) led me to imagine a new breed of field guides in which species descriptions would be penned by poets, not scientists.

Most of this succeeds as a multidisciplinary work “of imagination,” in which facts and myths are woven together. And, I was pleased, as a student of biology, to see ecological and evolutionary concepts referenced in the poems. For instance, the introduction of the invasive zebra mussel to the lake ecosystem and the irony of the resulting clearer lake water is addressed in “Seeing the Bottom off Thompson’s Point.” However, this phenomenon, one of the greatest ecological tragedies of many lake ecosystems in North America (“mistakes we made / in our youth”) is too briefly explored in only one poem, the shortest in the collection. Elsewhere, a line like “When evolution was yet to come,” which concludes an otherwise lovely elegy to ancient, fossilized life, is puzzling, as it suggests that this process began only when larger multicellular organisms appeared on land. The attempt to merge science and poetry is appreciated but sometimes falls short.

It is the more comprehensible human history of vessels and people that is conveyed most effectively, and then fixed in the lake mud. This long, relatively narrow lake has been crossed countless times; not all attempts succeeded. Lusk reminds us that when we cross water, we cross over a place to which we do not belong: a tomb, so easy to overlook. These poems take us there, from riotous squalls on the surface to the dark, muted lakebed of unseen wrecks and forgotten history.

— Christopher Hoffmann

Marengo Street: Selected Poems

by Anna Bat-Chai Wrobel.

by Anna Bat-Chai Wrobel.

Moon Pie Press, 2012,

paper, 89 pages, $12,

ISBN: 978-1-4507-8777-2.

Buy the Book

History slips by us like exits on an expressway — fleeting signs for towns and streets that we will never see since the accelerator is pressed to the floor and we are bent on arrival, getting where we want to be. As a history teacher and poet, Anna Bat-Chai Wrobel knows that too often we drive past what we need to remember. To counter our forgetting, she asks us to go where we do not want to go, and to see what we have conveniently forgotten.

Wrobel tells us of a world that holds the “unholy egg / conceived in Auschwitz,” where “legal minds / split . . . hairs over a definition of genocide.” She writes of a “crushed and ailing humanity” desperately trying to repair itself. We are asked to stop our headlong rush to be something or someone and to instead pay attention to what is happening to us. That is no easy task, since, often, our busyness is a way to avoid the horror surrounding us. And that is the question: How can any of us go on with our mundane activities when, if we pay attention at all to the news — to the violation of our land, of our fellow men and women, and of our children — we might as well throw up our hands?

Rather than throw up her hands, Wrobel embraces the world. In the poem “Rosh HaShana, 1992,” she contrasts fears for the new year with a lovely recounting of a day’s pleasures:

You know when you want that

hot morning shower to never end.

Or the baby to sleep on one

Evermore peaceful dreaming hour.

Times alone in clean rushing water,

Early morning solitude . . .

Soft whistling of

Little loved one breathing sleep.

She then contrasts such solace with the agony of knowing that:

We stand in hot morning showers

gathering splintering bones together.

Inhaling courage with the steam. . . .

And finally, she unites the two emotions: “Wearing anger as an amulet / and mercy as a glove.”

Living with a sense of history requires us to let the “ungloved hand / reach down inside,” to “see [one’s] open heart . . . in the strong slanting rays of / the sun we nevertheless share.” It requires knowing the essential in our lives. In “These Things First,” she captures such moments:

The first thing I have to do is make my bed

so when I return home

it may be unmade

in a ritual . . .

of closing what is open

and opening what is closed. . . .

That is the poet’s task, and it is the charge that Wrobel fulfills in this masterful collection: to let us see what is hidden and to make it fresh, so we can find acceptance — but never resignation — in what is wrong, as we strive to make it right.

— Bruce Spang