Polly Buckingham

Polly Buckingham: is the author of one book of poetry, The River People (Lost Horse Press), and two books of fiction, The Expense of a View (UNT Press) and A Year of Silence (Florida Review Press). She teaches creative writing at Eastern Washington University and is the editor of Willow Springs magazine and Series Editor for The Katherine Anne Porter Award. Her work appears in The Gettysburg Review, Threepenny Review, and The Poetry Review.

Paul Balfe

Paul Balfe: a child of the 60s, he grew up in Dublin, Ireland. He studied Medicine at Trinity College Dublin following which he trained and practiced as a surgeon in the Irish Healthcare System. He was awarded the September 2016 Irish Times Hennessy New Irish Writing Award for Poetry. His first collection, Four Seasons, was published in 2019.

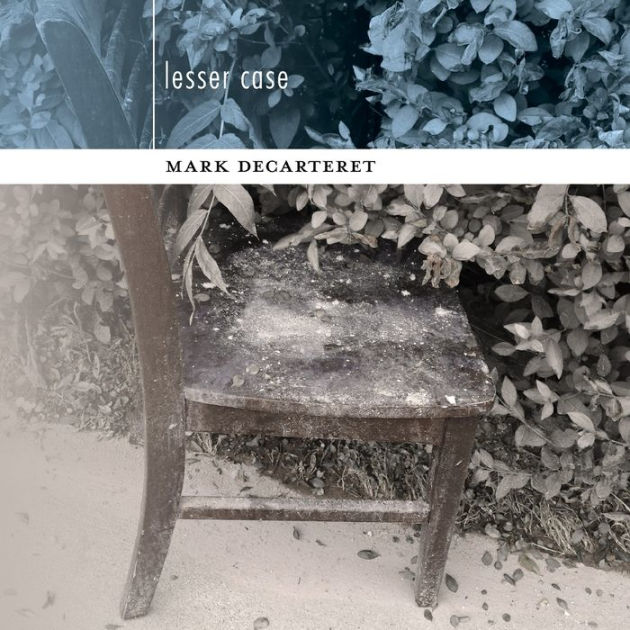

lesser case

lesser case

by Mark Decarteret.

Nixes Mate Books, 86 pages,

paper, $18, ISBN: 978–1–949279–30–6

Mark Decarteret’s new book is, in many ways, about the universe of the within as it projects itself out upon that larger one that surrounds us. In the process, the poet whittles away at the veneers of life, self, and art to find or, more importantly, to reckon with, the truths found underneath.

His is a voice that beguiles through image and motif to unmask passion in brilliantly indirect ways. I cannot find a more concise example of this than the poem “helium,” which comes early on in the book:

she still keeps a balloon

he filled up his last birthday

& every year since

takes in one of his breaths

& makes this similar wish

It is an image which is at once shattering and celebratory in its restraint. It is also typical of the punctuation–free, ampersand and slash–laced rhythm that moves the language along in these poems.

Throughout the book, Mr. Decarteret peals away at several recurring themes, or worlds: the world of existence, the world of relationships, and the world of truth which he ponders may, or may not, include himself. We can see this latter refection in the poem “drift,” which he dedicates to Wallace Stevens:

at least I got the world right

if only for a minute

thought it can’t be a coincidence

it happening

while I wasn’t in it

Another recurring motif in lesser case is that of the writer and his work as it pursues this truth, a pursuit that the poet is not always delighted with, as with the poem “breath”:

what luck these words

knocked off like air

not to mention

the great measure

one needs to pull

off a good poem:

putting just one

of those moments

back in their place

From the standpoint of structure, these poems display an expert economy of language and brevity. Rarely does a poem exceed a single page, and yet each page is its own soup can of the cosmos. This does not take place without a wry sense of humor, as we see in the poem “burden”:

even the most aggrieved ghost

has grown fearful over time

of the relocated chair

Or as further reflected in “winter haiku”:

here we have five or six

different words for snow

& they all start w/fuck

But the overall tone of lesser case settles in a quiet, contemplative grace that occasionally borders upon the elegiac. In it, the poet reckons with his own end in the same inside–out fashion that infuses the whole book — soul bare, winking up/winking down, as in “elegy”:

these fingers

last touched

the skin

which last touched

the bones

which will soon

touch the last

of any dirt

he’ll lie still for

lesser case rewards repeated readings as its layering unfolds in a sort of slant–accessibility that slows the reader down, like hovering a cursor over a video for a moment before the image starts to play — as in the poem “back (scratcher)”:

your littlest

plastic hand

on a stick

this itch all

I’ve still left

of that past.

— Craig Sipe

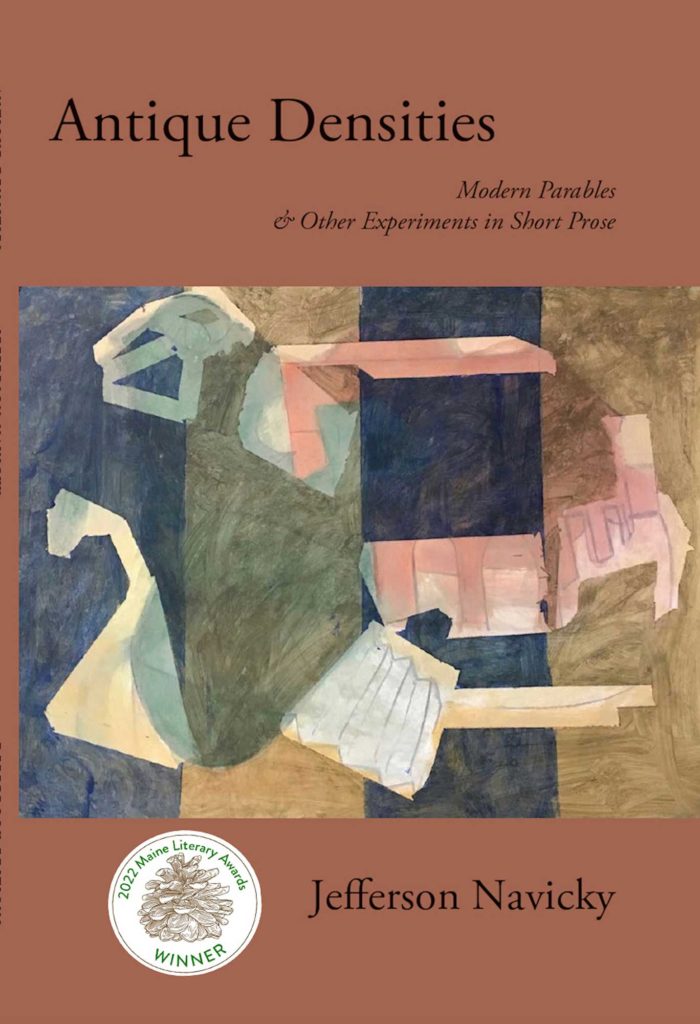

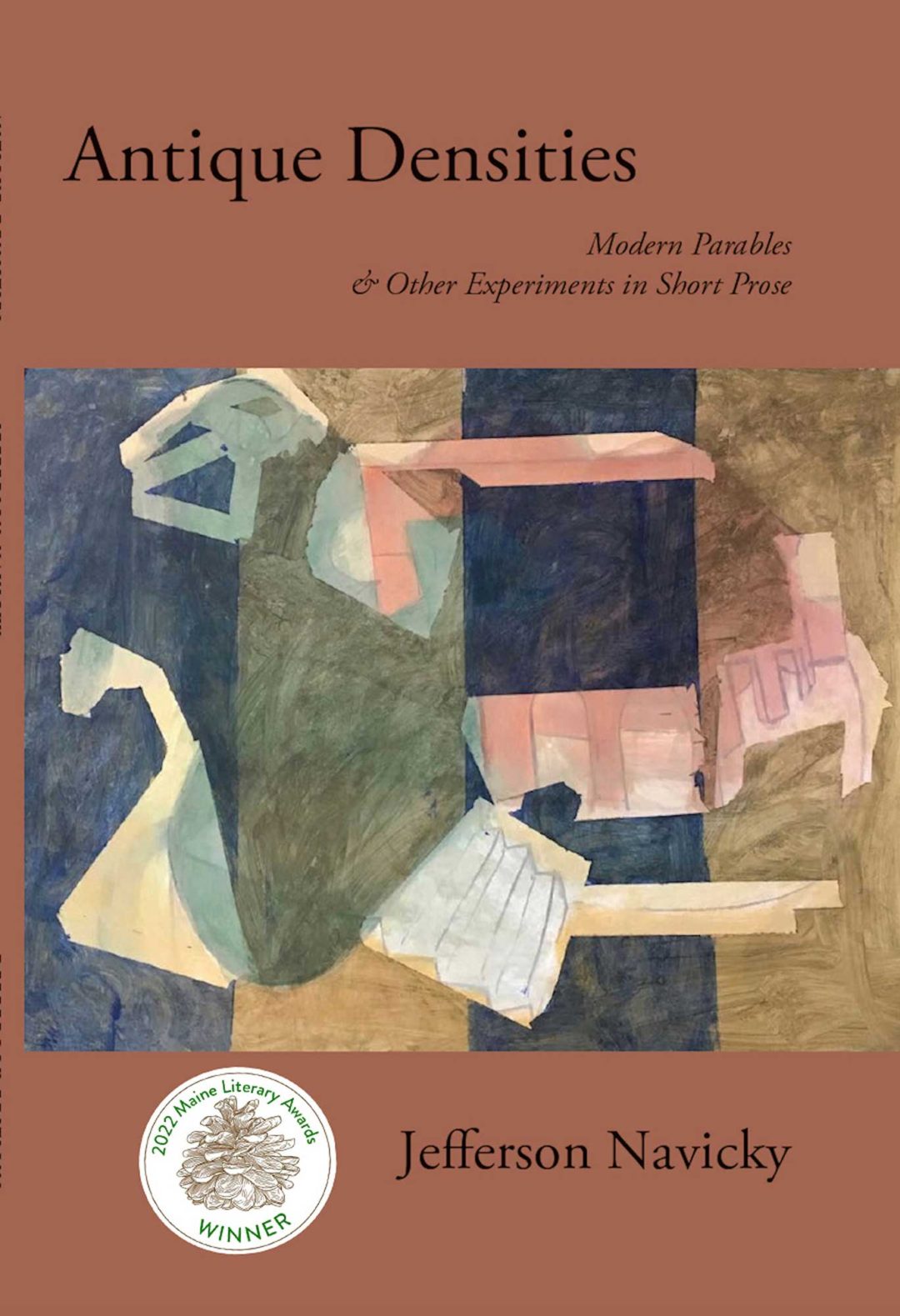

Antique Densities: Modern Parables & Other Experiments in Short Prose

Antique Densities: Modern Parables & Other Experiments in Short Prose

by Jefferson Navicky.

Deerbrook Editions, 2021

106 pages, paper, $18.50

ISBN: 9781736847725

Imagine trees spiraling sap inside book jackets, a forest thriving through your palm of paper. Antique Densities questions our answers, stripping down the logic in our lives. Are we the spines of stories, or are stories the spines of us? If you had little doubt about existence before, Jefferson Navicky’s archive of broken rules and shoulder–stretching metaphors will increase that uncertainty even more, in the most clever ways possible. With prose poems reinventing persona poetry, the hero’s journey, and objects as muse, Navicky reminds us that disappearance doesn’t always prove fatal; once–dismissed fantasies can actually be both explosive and hopeful.

Navicky’s rich unknowing halts time. After all, he was inspired by a book called Tales of Wisdom: 100 Modern Parables, which he found at twenty–two years old in New York City. Through sections titled “Books,” “Maps,” “City Directories,” “Transcripts of Oral History,” and “Special Collections,” the past and the future shake covers off the present, “creating echoes whose souls excited the hollow places of the house.” What would these rooms of language look like unconfined, our stories bound within breasts of birds? Navicky carves space into systems of everyday order, like a “grandfather clock where we make love, wedged between the huge hanging pendulum.”

We enter every paragraph with a new body: “You do not know if the train is in front of you, but you feel relief in knowing you are writing.” Through a variety of speakers — a barber, police officer, lover as thief, visitor’s book, boy dressed in his first words, mayor who wears snowshoes around the office, and even a hunched man — Navicky redresses solitude as creative inquiry. We’re driven to examine the peculiar in the familiar down to the very last drop. Through a single malt scotch on the rocks, a squinting dog on the floor of a café, or even a map that’s rescued and reused as a letter to a brother, Navicky teaches us to carry an abundance of lives within our own metamorphic retelling. “A rib cage floats in the air” is a perfect example of the uncontained and ever–changing physicality in this book. Navicky portrays humans as earth, paper, and history, unable to tell “what was at the heart beating beneath the wings. Was it knowledge or was it pain?” Antique Densities allows settling in the unsettling, how we can feel language with all our senses but still never be able to explain an experience. Navicky describes a book as “the moment he learned to touch” with “paper and skin flapping together,” showing the minute line between book and body. Ultimately, Navicky embraces the “twinned movements of language and fragility turning into each other,” furthering untranslatable landscapes of emotion rather than ones of theory.

With close attention to oral histories and faults of memory, Navicky’s work invites us to vulnerably enter new rooms of self–recognition while speaking to human limitations. We can never read everything; we often stare at screens to ingest two seconds of a story. Navicky poses: What if we started seeing books on the floor as casualties? What if all we altered of the natural world were our dreams, fossilized in mountain sides without ownership? By paradoxically placing enduring language inside ephemerality, Navicky welcomes return, suffering, expansive holding, and an unrealized freedom surviving any sticky shelf life:

“This was not our library. We walked through a hole in the

brick wall out

onto the street. A bus passed us. Our beginnings were

everywhere.”

— Amanda Dettmann