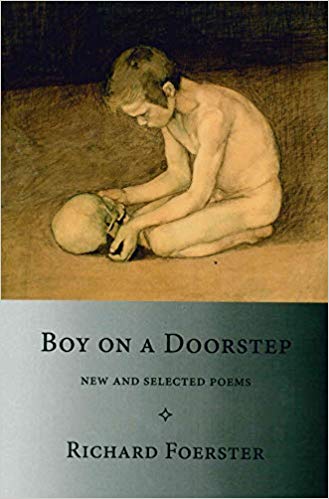

Boy on a Doorstep: New and Selected Poems

Boy on a Doorstep: New and Selected Poems, by Richard Foerster,

Tiger Bark Press,

264 pages, paper, $18.95,

ISBN: 978-1-7329012-1-6

Two things stand out about Richard Foerster’s poetry: his sense of rhythm and his storytelling. His collection Boy on a Doorstep offers illuminating retrospective and new looks into both.

Foerster, who is the recipient of NEA and Maine Arts Commission fellowships and has won Discovery / The Nation and Maine Literary Awards, writes in a strand of American poetry that grew from the modernist idea that the diction of poetry can match the diction of natural speech, but elevate it. By the postmodern 1990s, the emphasis was on the elevation, from which a diversity of skillfully crafted poetry emerged featuring fairly natural-sounding syntax cast in sentences that no English-speaking human being, however, would ever, in either the heat or the absence of any emotion, actually say. No one piles three, four, five dependent clauses onto the back end of a spoken sentence, even in informal lectures.

In this strand, one of Foerster’s special skills is coaxing normal speech rhythms into elevated poetic lines. This is oft attempted, but ne’er so well accomplished by most poets, at least not consistently. Foerster’s rhythms, though, have throughout his writing life been beautiful and natural. “I thought divorcing was an art worth perfecting /over time, like a vintage coaxed through fermentation,” opens “To Someone Somewhere After All These Years.” The first line is a sentence any English-speaker might say, the second slightly elevated in syntax but not unspeakable. At the same time, the rhythms in these lines are not bouncing meters, but they’re so finely given they might as well be. This skill is apparent pretty much throughout Boy on a Doorstep, selected from his books Sudden Harbor (1992) through River Road (2015), and several dozen pieces in a section titled “New Poems.”

Foerster’s many narrative poems are particularly forceful because the stories are so well told. Even the simplest recountings have a well-balanced sense of forward movement, or profluence, in their plots. In “Watercress,” the speaker of the poem while checking out at the grocery store is asked by the young cashier, “Did you find everything you were looking for? / . . . No, I said, looking deep into his earnest face,” and goes on to complain that the market does not seem to stock watercress. “What’s watercress?” the cashier replies, and this propels the narrator into an evocative, bittersweet reverie on youth and naiveté, ending on an everyday-language figure of speech cleverly used: “I knew to hold my tongue.”

An exemplary narrative is the elegiac “Tenure,” recollecting a love affair in France. The themes are memory, alcoholism, literature, regret, sex, and (a preoccupation, maybe) the dimensions of health. In this poem neither the profluence nor the flare of the language flags even in discursive asides:

If history’s an ever-swelling cyst that memory

must lancet open, I stitch it up repeatedly

each time I think of the pack-laden burro I was,

shambling through that sabbatical spring, up cobbled streets,

and I find myself cast within a slowly hardening past . . .

This is beautiful writing whose sense is not swamped by its sound. In fact, it’s enhanced. Form here arises from content, instead of hoping to create it by accident. This is the work of a master, and Boy on a Doorstep is the definitive entryway to his skill.

— Dana Wilde