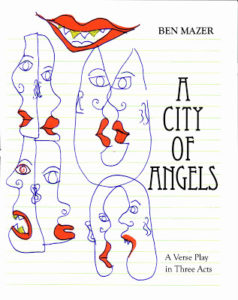

A City of Angels and How to Carve an Angel

A City of Angels,

A City of Angels,

by Ben Mazer,

Cy Gist Press, 2011,

36 pages, chapbook, $9

How to Carve an Angel,

by Peter Fulton,

The Seventh Quarry Poetry Press, 2011,

44 pages, paper, $16.90 (with CD of original musical compositions),

ISBN: 978–095674570–5

Because of the number of channels increasing every day on cable and computers, almost every person now has access to a video store in the house. In that position, like many couch – bound reviewers, I am confronted with the simultaneity of many — too many — works of art at my fingertips. In such an embarrassment of riches, it is refreshing to shift our focus to verse plays, which drastically limit our number of channels to the language of the poem in front of us, and to the music and voices that support that language. A renaissance of verse plays, revived in small theaters, and even café and home performances, could be a balm to our age.

When I started reading poetry in high school and college, verse plays were elusive to me, until I realized that I could simply suspend my disbelief and enjoy the language as it unfolded. Recently reading and seeing three successful verse plays performed confirmed how the form makes the language of lyric and narrative poetry even more accessible — and without elaborate productions.

In the case of Ben Mazer’s play, the channels are subtle and subjective: Nineteen – forties’ British dramas, Frost, Camus are the three I picked up, along with a hint of the Dudley Fitts translation of Oedipus. Which isn’t to say that a full scale tragedy ensues. The figure of interest is a young man, a tragic figure, who returns home to his destiny, which is to live the life of imagination — in this case to propose a play that no one can quite understand, but still they believe in him. The young man comes back with dreams that probably won’t be realized, but any tragedy is unnamed and depends upon each individual imagination:

. . . . Say this for the new drama:

It bought you fully to the edge of sense

where evils are met with indifference

and love has power to launch a new surprise,

intelligence communicated by the eyes

ignites the fire of activity

in the calm ticking of the calendar

released into the night’s ethereal

and blessing cognizance.

One can reread this verse play multiple times and experience the pleasure of the play building cyclically though the shape of “the new drama,” and the voices added to the voices that shape it. The cast consists of John Crick, who is the son of the best friend of John Wells, the president of a college. Crick returns to this college to propose a course in a life – defining “new drama,” but encounters the resistance of another group of townspeople. In addition, a family feud has broken out between the Cricks and the Crosses, and Crick’s father has been killed. Crick, then, is both a Prodigal Son and a Fisher King rolled into one. Likewise, many of the main characters, including Mary Wells, John Wells, and John Cross, are more archetypal than realistic:

CRICK: What keeps you at this place ?

MARY: The sound of the bells

Is like no other. The edge of the city’s walls

Instill a strong remembrance of things past.

I don’t know. I was a little girl here . . .

The minor characters function brilliantly as a chorus, supplying details that eventually coalesce into a lyric resolution, becoming part of the larger poem.

For that reason I would love to see this play simply read at a cafe by a dozen strong voices. No fancy production is necessary. I believe it would help an audience to have a brief sampling of each character’s voice, followed by some artful repetitions. Each stanza unfolds part of the action — but not all of it — so that you’ll want to read multiple times, each time finding more. A sophisticated young troupe with an ear for the musical play of dialogue could have much fun with these lines.

In the shadow of Dylan Thomas’ home town, Swansea, Wales, a number of verse plays were performed this year at the first Swansea Poetry Festival. Peter Fulton’s play “How to Carve an Angel,” Swansea’s production of which I watched on DVD, spends most of its energies in lyrics suggesting the inner weather of the sculptor protagonist:

They cannot imagine your revisioning

bursting thunder pinwheel’s cortex

skulling light reels of recollecting

No tick across your stoic mask

features your revelations’ revolt.

More of the scene is filled in by Fuller’s italicized stage directions that add precision, and the simple staging of Swansea’s low – fi production worked in service of the verse. The moving figures of the dancers firmly control center stage. Stage left, the characters are frozen in a tableau vivant. The reader and fiddler hover around the opposite edge, adding just enough to focus the audience on the complicated internal rhymes and the rising action: an angel sculpture being born. By the end of the play, the sculpture is firmly envisioned in the mind’s eye. The simple staging helps the audience focus on lines given to the Angel:

Did ignorance and want

ashame me into illusory seclusion

Are these torments my world’s

scrap of chips carved away:

everything that is not

my sculptor’s pure creation.

I could see both Mazer’s and Fulton’s plays having second lives as opera librettos. If that happens, my hope is that production values will not outstrip the words. And the form itself of the verse play, whatever its next incarnation, should not be overproduced. Nor should it be overwritten. It is tempting for a playwright to add more back story and to fill out the characters’ lives, but the verse play calls forth the gods of metaphor and synesthesia — the art of presenting one modality in terms of another.

Fortunately, both plays under review keep their focus on the language. Years ago I went to see a production of Amy Clampitt’s verse play in which she attempted to shine more light on the life and work of Dorothy Wordsworth. But the dramatic form was too elaborate, and at the end of the evening Dorothy was still overshadowed by William and the other Romantic poets. Clampitt had pointed out to me that each of Dorothy’s journal entries begins with a “weather tag,” like “A fine mild day.” However, in that night’s performance, Clampitt did not follow her own special insight into Dorothy’s language. Clampitt’s subject would have been better served by a less complicated play that focused entirely on her journals.

This leads me to formulate a rule of thumb for verse plays: Any production should not exceed the number of channels that the poetry supports. Start with The Poetry Channel. Then add in The Sculpture Channel or the Place Channel — not the other way around.

That is why I believe these two verse plays, whether on the page or minimally produced, are successful in their current forms. In this age of overproduced operas and music videos, here’s hoping we will see more ad hoc small companies form from these original productions. The Swansea group, including fine work by Peter Thabit Jones and John Dalton, is taking their verse plays to small but significant venues in America such as the Frost Farm in Derry, NH, and the Grolier Poetry Shop in Cambridge, MA. The first scene of Mazer’s “A City of Angels” first appeared on Eyewear (http://toddswift.blogspot.com/2010/08/ =verse – play – by – ben – mazer.html). If more small companies take such initiatives, more plays and scenes will be coming to a small playhouse or a cell – phone near us soon.

— Mark Schorr