Happy Life

by David Budbill,

by David Budbill,

Copper Canyon Press, 2011,

119 pages, $16.00,

ISBN: 978-1-55659-374-1

Buy the Book

It seems that the title of David Budbill’s latest volume of poetry tells the truth. It is not a sardonic commentary on life in the twentieth century. It is rather a collection of warm and accessible poems that grow out of the poet’s experience and his meditations on who he is and how he found himself over the last forty years. What keeps these poems from being just another man’s reflection on aging and vanished hopes is Budbill’s clear language, his wry, self – effacing humor and his humble recognition of all the poets to whom he owes his poetry. Oh, and it also includes verse dedicated to chainsaws, sex and ambition, and an over – riding arc of stillness in the face of natural beauty.

So what happens if you take a working class boy from Cleveland with a love of jazz and a penchant for Zen poetry to the woods ? Something like the poem “A Day Off,” which, after an opening of spring planting and endless work, work, work, opens its second stanza:

until, that is, I hurt my foot and now

I’m so lame I can barely stand,

which means, I have to spend the day in bed

with tea, the history of

Sung Dynasty poetry and the life of Yang Wan-li—

Showing once again how

misfortune

sometimes brings the opposite.

This is not to portray Budbill as out of the loop of current events. One of my favorite pieces in the book is the terse poem “Cynical Capitalists”:

Privatize profit.

Socialize loss. (40)

After listening to endless social commentary on the radio, it is comforting to read such a pungent distillation.

While to some these poems may seem uncomplicated, even simple, they have the feel of a thing made, filed sharp until the rough edges run smooth, then oiled until the words slide across the page. Too often I think contemporary poems run to the jagged and fractured, the overly complicated and dense. Sometimes the simple thing is all we need, and belief is all the poem asks of us. This is a lesson Budbill has learned in his forty years in the woods. It is not the only lesson, but it is an important one.

At times among these poems, we get to go to the city, as in “Three Days in New York: A Blues in B flat.” The poet wanders the city eating freight cuisine, pondering wonders of the non – European world at the Metropolitan Museum and musing: “Who told us Europe discovered the world ? ” But it is the final stanza of this longer poem that pictures the poet as he is:

And here I am this old white guy all decked out in my

yellow, orange, red, black, blue, and white dashiki

and my blue and gold African mirror hat playing

Japanese bamboo flute and ropes of bells from India

And a gong from Tibet, with these far – out, crazy

jazz musicians what come in how many different

shades of flesh and nationality, and me right here

on the Lower East Side in New York City reading my cracker,

woodchuck, honky, ofay, green mountains,

ersatz Chinese wilderness poetry.

Whatever David Budbill is, he is in the middle of it. Whether as an observer diving into his dreams, as a jazz musician, a poet, a playwright, a wood – cutting monk, or a scotch – drinking old man with his cheeks to the wood stove, he is all in. If we all went that far, wouldn’t it be a happy life ?

As he says in the sixth stanza of “Three Days in New York”:

Polyglot Gumbo Masala Stew

Hybrids Bastards Mutts All of us

All sloshed together Ain’t it grand ?

I, for one, need to be reminded of that.

— Michael Macklin

N.B. A Happy Life is the third in a series of books which also includes: Moment to Moment: Poems of a Mountain Recluse (1999) and While We’ve Still Got Feet (2005) published by Copper Canyon Press. Each of these is part of the chronicle of Budbill’s journey which involves spending nearly forty years on the side of a mountain in northern Vermont.

One With Others

by C.D. Wright,

by C.D. Wright,

Copper Canyon, 2010,

168 pages, paper, $18.00,

ISBN: 978–1–55659–388–8

Buy the Book

C.D. Wright’s One With Others, her portrait of one spitfire white woman in Civil Rights – era Arkansas, is not, she advises, a work of history: Rather, it is a “welter of associations,” a “report full of holes.” In this riddling of documentary, memory, and meditation, Wright returns to her native home as poet, investigator, and witness, to conjure her old mentor and friend V, an iconoclastic firebrand for literature and civil rights who in 1969 crossed the color line to join a civil rights march, and was driven out of town forever. Through interviews, news clippings, and her own recollections, Wright has crafted a book of verse with the momentum of fiction, by turns elegiac, slyly funny, and horrifying, in homage to V, a vibrant moral and cultural anomaly of her time and place.

That time and place is provincial Big Tree, Arkansas, smoldering with racial strife at a time of similar conflagrations across the nation. Wright calls it up through the words of radio ministers and the local veterinarian, with jokes and Dear Abby columns. She evokes it in its smells (“The faint cut of walnuts in the

grass. . . . The pulled – barbecue evening.”); its grocery prices (“A Whole fryer is 59¢.”; “Two pounds of Oleo, 25¢”); and the headlines (“Los Angeles enters its sixth day of rioting, 32 dead.”) She interviews the black man, a former state senator, who was beaten “by the sheriff who kept a man’s testicles in a jar on his desk until the word got around.”

As a woman and a homegrown intellectual in this world, V is fierce and ever – seething: “She woke up in a housebound rage, my friend V,” Wright tells us. “Changed diapers. Played poker. Drank bourbon. . . . Yeats she knew well enough to wield as a weapon.” V emerges through an array of recollections. From a friend: “Dragged her sewing machine to the porch because she did not want to have to look at it.” An old neighbor: “Oh yeah, I remember her, she celebrated all her kids’ birthdays on the same day.” Wright on her talk with another neighbor: “Flat out, she says, She didn’t trust me and I didn’t trust her. / Then she surprised me, saying, She was right. We were wrong.” The act that shunt V from much of the white community was to join a black organizer Wright refers to as The Man Imported from Memphis (aka “The Invader”) in The March Against Fear, a decision that got her her own headline: “WHITE WOMAN BACKS NEGROES, LOSES FRIENDS.”

Wright reveals V’s story and that of the March through a range of voices — friends from before and after her banishment, activists, and observers. Her storytelling is vertiginously non – linear, in fragments, verse, and prose poems that zoom in and out of time, that circle and refrain. The name of a movie playing in a segregated theater is forgotten one moment, but remembered some pages later; a radio preacher is possibly misheard (“Now get in that goddamn water and swim with the rest of them.”) Wright’s work is rich in changing tenses and shifts in narrators; her own voice withdraws for a time, then returns with an intimate lurch. Here, telling of V’s car blown up after the March: “She had just begun to drive, I mean she just learned to drive and she had many miles to go. Then whoa, Gentle Reader, no more car.” Wright’s piecemeal, circuitous narrative evokes the very shape and rhythm of memory, and the investigation of memory.

That investigation sometimes lands in a searing philosophy of the South’s ills. On the nature of institutionalized bigotry: “King called ‘it’ a disease, segregation. [sounds contagious] / It’s cradle work, is what it is. It begins before the quickening.” And on the emotional contortions of the regularly wronged:

. . . those so grievously harmed, who do the forgiving, do

so, that they not be deformed by the lie, must call on

reserves not meant to be tapped except for a

once – in – a – lifetime crisis. .. . .

But in this case, the reserves are needed every day, every hour of every day, because the warp is everywhere. . . . It is, in fact, the law.

By a gradual accumulation of glints and fragments, Wright also reveals a culture and V over time, the grown children of Big Tree and V ever – rebellious in 2004, on her deathbed in a one – room Hell’s Kitchen apartment. In these moments, there is the temptation to find relief in the contemporary, in having caught up in time to a saner, reason – driven present, the after to the before. But in Wright’s magnificent, important “welter of associations,” in the jukeboxes, radio, and people she hears in today’s Big Tree, there is a stark reminder that history’s shifts, its remembering and forgetting, its outrages, are inextricable from a modernity that’s anything but finished:

Sound of the future, how close

to the sound of the old. . . .

— Megan Grumbling

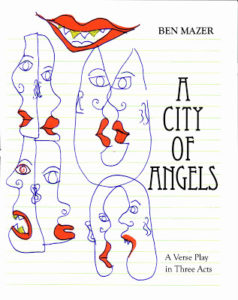

A City of Angels and How to Carve an Angel

A City of Angels,

A City of Angels,

by Ben Mazer,

Cy Gist Press, 2011,

36 pages, chapbook, $9

How to Carve an Angel,

by Peter Fulton,

The Seventh Quarry Poetry Press, 2011,

44 pages, paper, $16.90 (with CD of original musical compositions),

ISBN: 978–095674570–5

Because of the number of channels increasing every day on cable and computers, almost every person now has access to a video store in the house. In that position, like many couch – bound reviewers, I am confronted with the simultaneity of many — too many — works of art at my fingertips. In such an embarrassment of riches, it is refreshing to shift our focus to verse plays, which drastically limit our number of channels to the language of the poem in front of us, and to the music and voices that support that language. A renaissance of verse plays, revived in small theaters, and even café and home performances, could be a balm to our age.

When I started reading poetry in high school and college, verse plays were elusive to me, until I realized that I could simply suspend my disbelief and enjoy the language as it unfolded. Recently reading and seeing three successful verse plays performed confirmed how the form makes the language of lyric and narrative poetry even more accessible — and without elaborate productions.

In the case of Ben Mazer’s play, the channels are subtle and subjective: Nineteen – forties’ British dramas, Frost, Camus are the three I picked up, along with a hint of the Dudley Fitts translation of Oedipus. Which isn’t to say that a full scale tragedy ensues. The figure of interest is a young man, a tragic figure, who returns home to his destiny, which is to live the life of imagination — in this case to propose a play that no one can quite understand, but still they believe in him. The young man comes back with dreams that probably won’t be realized, but any tragedy is unnamed and depends upon each individual imagination:

. . . . Say this for the new drama:

It bought you fully to the edge of sense

where evils are met with indifference

and love has power to launch a new surprise,

intelligence communicated by the eyes

ignites the fire of activity

in the calm ticking of the calendar

released into the night’s ethereal

and blessing cognizance.

One can reread this verse play multiple times and experience the pleasure of the play building cyclically though the shape of “the new drama,” and the voices added to the voices that shape it. The cast consists of John Crick, who is the son of the best friend of John Wells, the president of a college. Crick returns to this college to propose a course in a life – defining “new drama,” but encounters the resistance of another group of townspeople. In addition, a family feud has broken out between the Cricks and the Crosses, and Crick’s father has been killed. Crick, then, is both a Prodigal Son and a Fisher King rolled into one. Likewise, many of the main characters, including Mary Wells, John Wells, and John Cross, are more archetypal than realistic:

CRICK: What keeps you at this place ?

MARY: The sound of the bells

Is like no other. The edge of the city’s walls

Instill a strong remembrance of things past.

I don’t know. I was a little girl here . . .

The minor characters function brilliantly as a chorus, supplying details that eventually coalesce into a lyric resolution, becoming part of the larger poem.

For that reason I would love to see this play simply read at a cafe by a dozen strong voices. No fancy production is necessary. I believe it would help an audience to have a brief sampling of each character’s voice, followed by some artful repetitions. Each stanza unfolds part of the action — but not all of it — so that you’ll want to read multiple times, each time finding more. A sophisticated young troupe with an ear for the musical play of dialogue could have much fun with these lines.

In the shadow of Dylan Thomas’ home town, Swansea, Wales, a number of verse plays were performed this year at the first Swansea Poetry Festival. Peter Fulton’s play “How to Carve an Angel,” Swansea’s production of which I watched on DVD, spends most of its energies in lyrics suggesting the inner weather of the sculptor protagonist:

They cannot imagine your revisioning

bursting thunder pinwheel’s cortex

skulling light reels of recollecting

No tick across your stoic mask

features your revelations’ revolt.

More of the scene is filled in by Fuller’s italicized stage directions that add precision, and the simple staging of Swansea’s low – fi production worked in service of the verse. The moving figures of the dancers firmly control center stage. Stage left, the characters are frozen in a tableau vivant. The reader and fiddler hover around the opposite edge, adding just enough to focus the audience on the complicated internal rhymes and the rising action: an angel sculpture being born. By the end of the play, the sculpture is firmly envisioned in the mind’s eye. The simple staging helps the audience focus on lines given to the Angel:

Did ignorance and want

ashame me into illusory seclusion

Are these torments my world’s

scrap of chips carved away:

everything that is not

my sculptor’s pure creation.

I could see both Mazer’s and Fulton’s plays having second lives as opera librettos. If that happens, my hope is that production values will not outstrip the words. And the form itself of the verse play, whatever its next incarnation, should not be overproduced. Nor should it be overwritten. It is tempting for a playwright to add more back story and to fill out the characters’ lives, but the verse play calls forth the gods of metaphor and synesthesia — the art of presenting one modality in terms of another.

Fortunately, both plays under review keep their focus on the language. Years ago I went to see a production of Amy Clampitt’s verse play in which she attempted to shine more light on the life and work of Dorothy Wordsworth. But the dramatic form was too elaborate, and at the end of the evening Dorothy was still overshadowed by William and the other Romantic poets. Clampitt had pointed out to me that each of Dorothy’s journal entries begins with a “weather tag,” like “A fine mild day.” However, in that night’s performance, Clampitt did not follow her own special insight into Dorothy’s language. Clampitt’s subject would have been better served by a less complicated play that focused entirely on her journals.

This leads me to formulate a rule of thumb for verse plays: Any production should not exceed the number of channels that the poetry supports. Start with The Poetry Channel. Then add in The Sculpture Channel or the Place Channel — not the other way around.

That is why I believe these two verse plays, whether on the page or minimally produced, are successful in their current forms. In this age of overproduced operas and music videos, here’s hoping we will see more ad hoc small companies form from these original productions. The Swansea group, including fine work by Peter Thabit Jones and John Dalton, is taking their verse plays to small but significant venues in America such as the Frost Farm in Derry, NH, and the Grolier Poetry Shop in Cambridge, MA. The first scene of Mazer’s “A City of Angels” first appeared on Eyewear (http://toddswift.blogspot.com/2010/08/ =verse – play – by – ben – mazer.html). If more small companies take such initiatives, more plays and scenes will be coming to a small playhouse or a cell – phone near us soon.

— Mark Schorr

Impenitent Notes

by Baron Wormser,

by Baron Wormser,

CavanKerry Press, 2010,

87 pages, $16.00,

ISBN: 978–933880–23–5

Buy the Book

I first encountered Baron Wormser five years ago at a talk he gave at the Portland Public Library, in Portland Maine, about his book The Road Washes Out in Spring: A Poet’s Memory Living Off the Grid.

I was fascinated by his unassuming account of living with his family for nearly twenty – five years in a house in Hallowell, Maine, without electricity or running water. They carried water by hand, grew much of their own food, and read by kerosene light, settling into a life that centered on what Thoreau had called “the simple facts.” Yet ironically, as Wormser claims, their choice to “live off the grid” was neither statement nor protest: they just happened to have built their house too far back to afford to bring in the power lines.

Over the years, Wormser has been described as a realist whose poetic voice is rooted in everyday life, popular culture, and the emotional complexities of ordinary people. In his ninth poetry collection, Impenitent Notes, the former poet laureate of Maine, who is widely published and the recipient of numerous prestigious literary awards, leaves the impression of a man comfortable in his own skin, yet equally perplexed, angered and enlivened by the world around him.

Many of his perceptions in these poems profoundly capture men and woman in a state of social, political and economic crisis. In “Ode to Time,” Wormser writes: “You’ll get to sit around the assisted – living facility / and make bets on who will go next.” He writes about “another Republican president / who squares morality with greed and smiles about it,” then remarks: “Time is an ugly polluted river.” In his poem “Evenings,” he observes: “Futility rises as well as anyone in the morning.”

In his especially poignant poem “Millions,” he contrasts the lives of a hedge fund millionaire and owner of a tree service company with “a few poets / who have mastered the trick of living solely on oxygen”:

. . . When a ten – dollar check

Comes in the mail for a poem they laugh and use it

To start a fire in the Jotul of blow – down —

Wood that lived its life without cash whatsoever,

That grew from random seeds that blew in the wind.

His poems cover an impressive range themes, such as the

still – sensitive issue of gay awareness in “Winning”:

It is Thanksgiving

The day the family salutes the notion of family

And I was invited as Rick’s college roommate.

Rick, who was gay, told me he was going to tell

His folks officially and wanted someone straight

To be there to “thin out the flak” in Rick’s words.

Later, the father and mother of the gay son retire to Florida, where he still builds model fighter planes and she bakes pies. And:

Rick’s been with the same guy for over a decade

And sends me Christmas cards each year

In which he frets about his waist size.

Like many great poets, Wormser doesn’t avoid difficult subject matter (“Subject Matter” being the actual title of one of his earlier collections) — a mother succumbing to cancer, Americans being ripped off by Wall Street, torture in Latin America, the murky life of prostitutes, the despair of the mother of a soldier killed in Iraq. Indeed, Wormser often startles us with how people tend to dodge challenging subjects, as in “The Oil Man”:

Every drop of oil is the earth’s blood, a sensitive

Girlfriend once told me while I was putting a quart

Into my ‘64 Ford. Is that good or bad ? I asked her.

Sometimes it’s hard to make sense of metaphor.

No wonder it largely keeps to poetry.

The absurd unreality that advertising offers its viewers and its debilitating effect it can have on the psyche is well captured in “Bud Light”:

The guy who is buying a twelve – pack at the convenience store

On a Wednesday evening isn’t listening to why we are

The way we are and how, through words and sincerity,

We could get better. Even as he puts his hard – earned down

On the slightly greasy, Formica counter

He’s already sitting on front of the TV

Drinking one beer after another, quickly.

Readers have become accustomed to Wormser’s range, depth, and uncanny ability to get inside the hearts and minds of his characters. As his probes beneath the skin of simple folk, we see our shared aspirations, disappointments, and defeats, as well as the maddening controlled and uncontrolled influences that threaten to consume us, in a new and refreshing light. And as the word “impenitent” implies, the author achieves this without regret, sham or remorse.

— Leigh Donaldson