The Great Contender

By Stephen Bett

The man who shot Liberty Valence

clearly didn’t care mucho much for Valencia

(nor likely cross–town rivals VillaRReal)

That derby hall a’ miRRors . . . a’gin & redux

When Val rode to town the womenfolk would hide

(Rreal men & transfolk, they’d abide onside)

Give me hibbity jibbity or give me the point of a gun

the only law that [libs] understand —

lib•bard•y for not from dems wackos

Rrose Sélavy likely–wise cried snide

in zir Yellow Submarine

(it’s true, #LookItUp!)

Putt it right on the platter

The man who flipped a birdie on yr Lib Pal

— poor Burt Bacharach, dead

at 94 just this week —

He was the [gravest] man of all

he was the Great Contender

Just laughing and gay like a clown

in my town*

*Gene Pitney, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence” & “The Great Pretender” (the latter also covered by The Platters, & both songs written by Burt Bacharach); properly speaking, Valencia & Villarreal Club Futbol are cross–region derby rivals (the latter’s motto: “The Yellow Submarine”); & fondly recalling Grade 4 club Membership Card for “The–Look–It–Up–Club” (motto: “We Don’t Just Guess, We Look It Up!”)

Plaques You Won’t Find on the Shore of the Penobscot River in Bucksport

By Rick Doyle

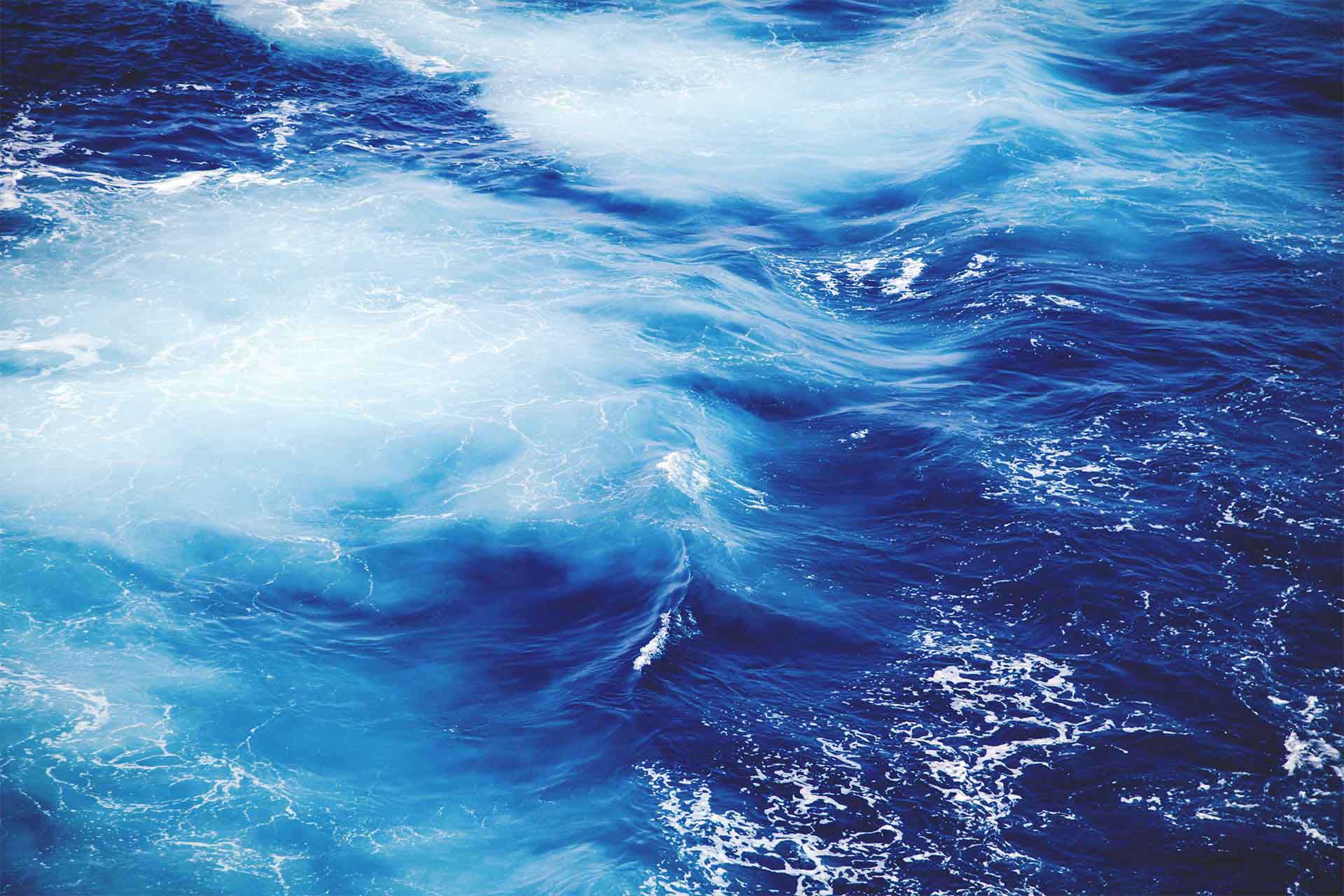

Here the sagging shag–lined wharf

got dismantled after the war

by square dancers planning to erect

a clubhouse on Verona Island.

This is where one winter day a deer}

pursued by a ragged pack of dogs

was forced to flee across the river

on the tide–lifted havoc of its broken ice.

Here grew the crooked cherry tree

from which once upon a time

after the loss of a phoebe’s favor

a river pilot’s stiff pea coat was hung.

Here lay sturgeon dreaming long

salt snowfalls of slow metallic silt,

gulls and seals and rossed spruce torsos

gone swimming seaward overhead.

Listen. Above the basso profundo

of the sulfurous pulp and paper mill

ferrymen sing, as they pole,

the most popular arias of their day.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: Juan-les-Pins, France. November, 1926

By Debra Conner

Hemingway’s a fake, Zelda claims,

a pansy with hair on his chest,

a professional he man.

Hadley’s his minion, she says,

his substitute mother, his trust fund wife.

Zelda fumes when I pick up their tab.

Tonight, after Zelda stormed out

of the restaurant, and Hadley left

with the baby, Hemingway

sidled over to say my wife’s bad news.

She’ll ruin me, he warned, with her antics,

her need for attention.

She’s the reason I struggle to write.

Hemingway’s the golden boy now, gilded

with success from The Sun Also Rises

and I’m just a name on a guest list.

He’s flaunting a bruised chin

and a bandaged hand from the boxing ring.

The tape’s as white as his face

the day I drove us to the cliff ’s edge

and braked with one front tire dangling.

Now, he pats my arm like he’s my best pal.

He snaps a match and lights my shaking cigarette.

On my plate, my half–eaten steak grows cold.

Zelda Fitzgerald: New York, NY. April, 1922

By Debra Conner

At the Tribune editor’s urging, I penned

a satiric review of The Beautiful and Damned,

joking about Scott’s habit of plucking

passages from my letters and diaries.

The newspaper’s folded open on the table

and I reread my best lines:

Mr. Fitzgerald — I believe that’s how

he spells his name — seems to believe

plagiarism begins at home.

I tried to keep it light, to ignore

the editor’s note that I’m Scott’s wife.

Buy the book, I urge the readers,

I need that gold dress in Bergdorf ’s window,

that splashy platinum ring.

Scott’s out and the baby’s asleep, so I trash

the rubble of butts and bottles. My head throbs.

My name on the page contracts and expands.

A broken glass bloodies my hands.