Mike Bove

Mike Bove: is the author of two books of poems: Big Little City (2018) and House Museum (2021). His work has appeared in journals in the US, UK, and Canada, and he was winner of the 2021 Maine Postmark Poetry Contest. He is Professor of English at Southern Maine Community College and lives with his family in Portland, Maine where he was born and raised.

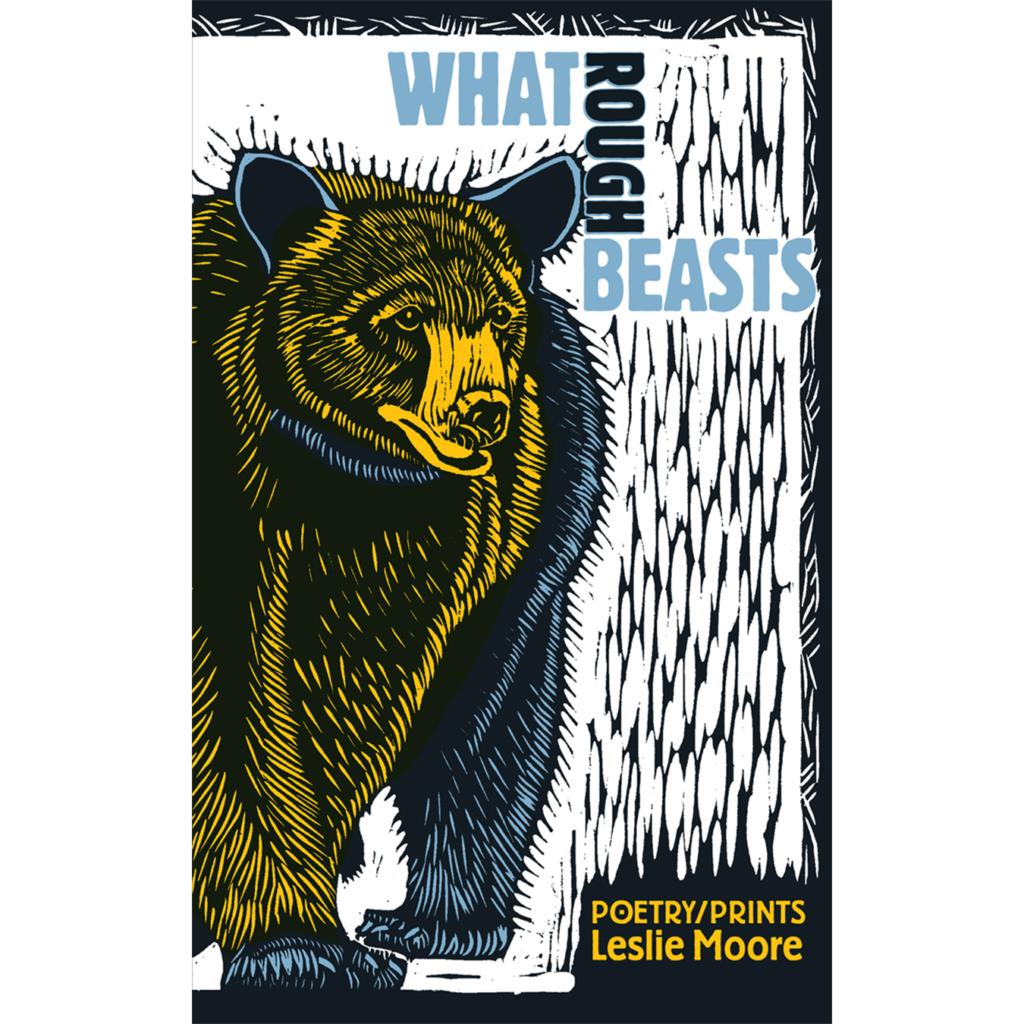

What Rough Beasts: Poetry/Prints

What Rough Beasts: Poetry/Prints

by Leslie Moore.

Littoral Books, 2021,

70 pages, paper, $18.95,

ISBN: 978–1–7357397–4–8

The title of Leslie Moore’s book comes from Yeats’s famous poem “The Second Coming.” It’s a bit misleading: In the context of the Irishman’s verse the three words connote apocalypse, whereas Moore’s creatures are for the most part welcome inhabitants of her Maine world — rough around the edges, perhaps, but beloved, nonetheless.

That said, the title poem, with its evocation of a U.S. president inciting a coup, makes Yeats’s dark vision once more relevant. That insurrection and a red–tailed hawk gyring over the blueberry barrens atop Beech Hill in Camden prompt the poet to state “a hundred years and the center still does not hold.”

The book’s opening section, “Naming Birds,” conjures close encounters of the bird kind. Crows receive the most attention. Moore adds to the rich line of corvid poetry (Ted Hughes, Louise Bogan, et al.) with such poems as “Oracle” and “Riddle of the Crow.” In the first, the bird in Japanese artist Ohara Koson’s print Crow on a Snowy Bough speaks to her, but she only hears it “when I wake from my sleepwalk, / when I pause, / when I become / the caw.” In the second, a local crow nurtured on kibbles is “a black panic in feathers.”

A sense of play and humor marks a number of poems. “Naming Birds” questions the decision to call a “carrot–topped bird / in his herringbone jacket and ashy underpants” the Red–Bellied Woodpecker. Moore suggests an alternative, “Orange–Coiffed Woodpecker,” whose swagger recalls Cyrano de Bergerac: “Both flaunt notable noses / and plenty of panache.”

In the two subsequent sections, “Visitations” and “Totems,” Moore’s menagerie expands to include fox, bear, flying squirrels, a glass eel, garden spiders, frogs, and other animals found in her Belfast neck of the woods. She is inventive in her imagery: tadpoles squirming inside their eggs are “like crazed commas trying to escape the lines of a poem.” And “Animal Tracks in Snow” delineates the various “fine traceries” of her animal neighbors as they make their way here and there.

Moore ends several poems with an expression of wonder. A chance meeting with a yearling moose leaves her “incandescent”; after watching a loon land on the water, she writes, “I can’t catch up / with my heartbeat.” In “Eastern Milk Snake,” four “fearsome feet” of Lampropeltis triangulum triangulumin the compost pile sets the heart “hammering.”

Moore turns to ekphrasis on a couple occasions, most notably her riff on Dahlov Ipcar’s painting Blue Savanna in the Portland Museum of Art collection. In 18 lines she captures the dazzle of Ipcar’s composition where “wildebeest careen over indigo veldts / zebras zig–zag sapphire shards.”

The tradition of the poet / artist goes back at least to William Blake and his “Tyger.” Moore carries it on with her knock–out combo of verse and linocuts. Recalling some of Holly Meade’s woodcuts, a charming “woodchuck non grata” accompanies a poem about the raids the animal makes upon the fresh vegetables at Rebel Hill Farm in Liberty, Maine. Barn Owl Nocturne and Red–Tailed Hawk in Snow emulate Japanese artists.

Earlier this year, granddaughters Maria and Serita sent my wife and me handwritten transcriptions of two animal poems, “The Little Turtle” by Vachel Lindsay and “The Frog” by Hilaire Belloc. They were reminders of how especially cherished animal poems are. With What Rough Beasts, Moore adds to that precious inventory.

— Carl Little

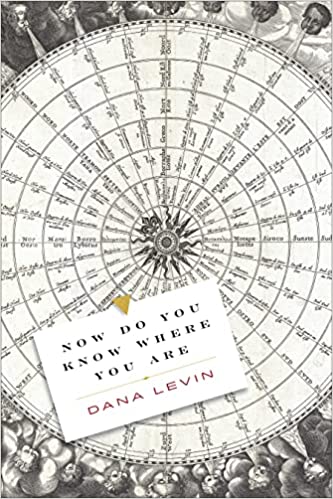

Now Do You Know Where You Are

Now Do You Know Where You Are

by Dana Levin.

Copper Canyon Press, 2022,

92 pages, paperback, $17.00

ISBN: 9781556596339

In Tillie Olsen’s Silences, an eccentric, broadly–researched, masterful book published in 1965 about why writers (especially women) don’t write, Olsen states, “Extremity. When overborne, overworn — for a period — one breaks down, gives up, goes under, cannot go on.”

Dana Levin knows what Olsen is talking about. If we’re honest with ourselves, all writers know the precariousness of the writing life. One physical set back, one financial pitfall, one mental health crisis, and a writer can easily absent themselves from the page for years. To write is nothing more than an exercise in persistent presence with the page, but it involves much more luck than anyone would like to admit. In Levin’s fifth collection, Now Do You Know Where You Are, she walks that fine line between writing and silence for ninety–two pages. It’s a thrilling, doubt–filled, harrowingly honest walk.

The book begins in the aftermath of the 2016 election. By January 2017, the poet is in trouble, and so begins the ten–and–a–half–page journalistic poem, “Pledge.” The poet takes the eponymous pledge because her sister “made me take this pledge . . . to write every day for twelve weeks about your feelings (blech).” So much gets expressed in that parenthetical “blech” — is it a burp? A gagging finger down the throat? A casual vomit sound a poet makes when shoehorned into prose? Despite trepidations, the poet follows the pledge dutifully, and while every day doesn’t make it into the poem version, a reader can easily sense the poet’s state of mind:

March 6

Sitting with C., drinking early morning coffee, talking about not being up for the task of being us in this postelection environment, conflict avoidant and inward and hermetic, burrowers, hiders

The passage almost sounds like an introvert’s manifesto, but what’s important to note is that Levin does not fall victim to the silences that Tillie Olsen chronicles. Instead, rather than allow the troubled state of the world to clam her up, she over and over again finds a way to maintain her contact with the page.

The extent of this doubt should not be overlooked. The book is shot through with it. In “For the Poets,” a poem that hoarse whispers in all us poets’ ears, Levin writes, “if only three people like a tweet does anything you offer sound in the forest?” This is the kind of doubt that heads straight to the heart to ask, “why . . . do any of us do any of this?”

Another multi–page, prose–y poem in sections, “Appointment,” speaks deeply to this question, and offers a hero, of sorts, the Body Worker / Mystic Healer Jensen: “Tall and lanky, and his face, in profile, looked like a hawk’s.” He is, in his own words, an “Incarnation Specialist,” who works with the poet to let herself “be completely rewired.” There is much to admire in this poem, from the loose but sincere manner with which it handles the spiritual to the degree of depth it dives into personal story. Yet again, I was drawn to her thoughts about poetry and her trouble writing it: “poetry, marooned inside me. I’d been having so much trouble writing . . . being afraid to write because someone would see it (after four books!)” And while Jensen helps her to be born again as a poet, she also bravely helps herself by staying inside the doubt, finding a way to write in spite of it, and finding a way to allow poetic form to reflect the self.

While there are pages and pages of prose chunks that toe the line between a poem and a journal entry or a lyric essay, Levin also possesses a strong intuitive, experimental expression of line and punctuation. I love the scintillating juxtaposition such disparate forms create in the same book. In the jaw–droppingly austere “Instructions for Stopping,” the pressing physical danger of possible gun violence stretches out into the air as Levin draws the poem out on the page with short lines, spacious stanza breaks, and dashes that Dickinson your breath away. “Your Empty Bowl” goes even further down the line of possible dash usage by interrupting syntax with what seem like section breaks, but are really hyper–extended and drawn out dashes. The effect is like falling down stairs as a snowman.

To end, I want to return to “Pledge,” which turns out to be a poem about the speaker’s agony about putting down her beloved cat. A friend gives the speaker this advice, “maybe what we need is to feel a poet’s love for her dead cat. Haha! But seriously.”

Yes, very seriously. Yes.

— Jefferson Navicky

The Leviathan

by James Brasfield

First summer after the lottery

numbers were assigned,

and each day the country was

closer to what was called

Peace with Honor — at its end

nearly 60,000 soldiers lost —

I was a lifeguard at the inner–city pool,

and off from my tall chair

saved, from what I remember,

a little girl just in over her head

and a man on the grate

at the bottom of the deep end.

Fifty years and twelve–hundred miles

from the pool, I see my town’s bay

from my window and someone

walking down the sidewalk

on the other side of the street

(on its berm a line of trees),

someone who doesn’t live

along this street, pass behind a tree,

appear, then pass behind another

and on until mid–block, and disappear . . .

I was issued a number

too high for conscription. —

Six years later, Saigon fell.