Eye

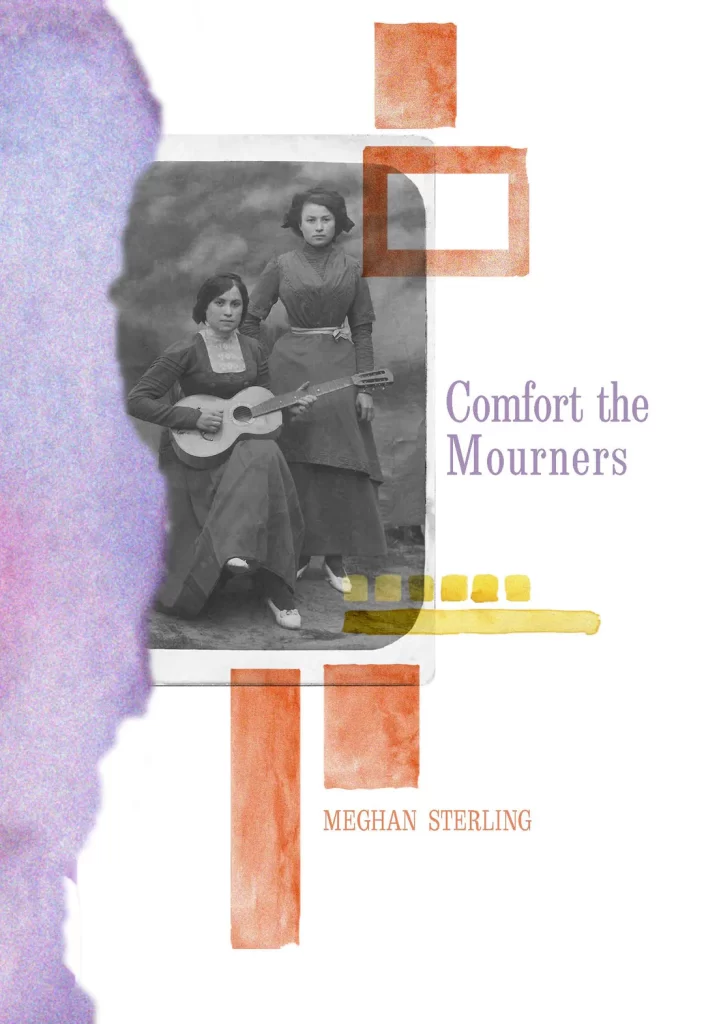

Eye, by Mike Bove.

Spuyten Duyvel, 2023,

94 pages, paper, $17,

ISBN: 978–1–959556–80–0

Mike Bove’s third collection of poems, Eye, carries two epigraphs: a notice in the Portland Press Herald of an impending early March snowstorm and this quote from poet Charles Simic: “Imagination doesn’t create. It sees connections to what is already there.” Together, these citations provide a nice set–up for what unfolds in the 51 poems that follow: encounters with a winter blast and the visions that emerge and ensue.

Snow–related poems abound. In “Plow Drivers” Bove pays tribute to the folks who clear the streets and their “angel’s wing of steel” which “descends to the road / in the sacred name of / clearing and passage.” Another poem, “Thundersnow,” draws attention to the phenomenon of rumbles in a snowstorm.

the sky in storm is worth our pause

there are things in nature

we rarely see despite hearing

stories and when at last we do

no matter for god or thunder

reverence is reverence

“Empty Churches” evokes a retreat from the blizzard. The final lines might be a summary of Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going”: “if you want to learn / what wonder is // find an empty church / and leave it.”

In amongst these snowbound reflections Bove conjures the past. The remarkable “Field Guide to Roadside Geology” contains several vivid memories: falling from a shopping cart — “my poor little self that once knew freedom / thereafter broken” — mining gemstones in Maine’s western mountains, and finding “treasure jewels” in sandy rivulets while lying in the street after a heavy rain. Pain and beauty go hand in hand here.

A number of poems relate to sight and seeing. In “Emily Dickinson Upstairs,” Bove revisits the story of how the poet almost lost her vision, a brush with blindness that ends with

the triumph of light

when the words did appear

and she spoke them out

in that sun–bright room where

sight had turned to song

Bove substitutes “eye” for “I” in a number of poems. As he explained in an interview with Jefferson Navicky in Hole in the Head Review, “‘Eye’ in some of the poems becomes a stand–in for our remembering selves.” So it is in the poem “Borderland” where the “eye” acts as a kind of distancing mechanism for dealing with a father who instilled fear in his son: “when he got old / eye / understood // better // who he’d been // and why he / loved // and who.”

Bove’s poems are often spare, with a Williams/Creeley/Levertov quality to the way the lines tack down the page. Here’s the ending of “Get Down,” inspired by wind in the trees:

it’s a woodland soirée

a deciduous two–step

and the wind sets

the tempo to arrhythmic

shuffle and who cares

that no one else

can hear it

just because

they can’t

doesn’t mean

it’s not music

In an afterword, Bove notes that the poems in Eye were written over five days “immediately before, during, and after the last major snowstorm of the year.” His “mind of winter,” to borrow from Stevens’s “The Snow Man,” leads to some beauties, including “Mourning Dove,” “Out,” “Outage,” “Tree,” “Walking at Night,” “A Boy Implores,” “Night Manager,” and “Warming Hours.” “Eye of the Storm” offers the best snowstorm advice:

rejoice and revel

claim this rapture

if you’d stayed inside

you’d have missed

this precious gift

of sight.

—Carl Little

Comfort the Mourners

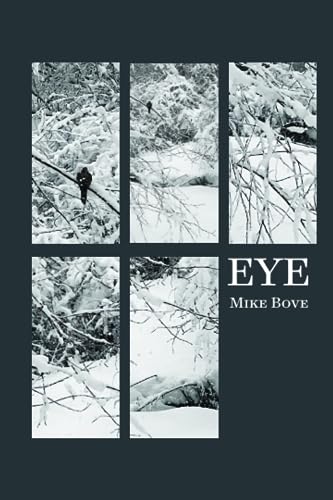

Comfort the Mourners, by Meghan Sterling.

Everybody Press, 2023,

84 pages, paper, $24.00,

ISBN: 9781956639117

It can be argued that poets only ever write about the past — now slips quickly into then in the very act of writing — and every story a poet tells, about themselves or someone else, is forever rooted in some awareness or experience from before. Themes of time and memory layer Meghan Sterling’s Comfort the Mourners, a collection that explores what it means to fully participate in one’s past.

In “Biography,” the book’s opening poem, these themes appear immediately. Sterling offers a litany of things remembered, a catalog of connected objects and events that begin the speaker’s story:

[. . .] How many stories.

The ancestors’ escape from Ukraine, the dead,

the lovers, the houses, the states, the cars, the

journals that recorded their everything on yellow

paper, now burned.

Many of the subjects are deeply personal, and in them Sterling confronts a past that has led to a present of daughterhood, motherhood, partnerhood, and personhood. The war against Ukraine is of immediate concern in several of the poems, as are unanswered questions about one’s autonomy in a world that seems bent on oppression. What does it mean, for instance, to attempt to heal from the suffering of one’s ancestors yet still be expected to mount a defense against the ongoing ignorance that caused it? In “Flinging Myself Against You,” the speaker confronts that question and more:

I’ve died so many times already that I’m certain

the last time will shiver hollow, the final peal

of a bell rung a thousand times, chiming out

like the bright blue squares of stained glass

in the church where I attended preschool, the one

[. . .] where I had to explain again and again that I

hadn’t killed Jesus.

Sterling’s meditations on ancestry range from lament to celebration, and the lasting impact is the understanding that heritage, however tragic or beautiful, perilous or secure, is indivisible from one’s current self; heritage is always the recent past of personal identity. And that, too, is always changing, undulating like a river’s current. Indeed, images of water abound in these poems, a fitting reminder of time’s fluidity and a source of comfort in uncertain times, as in “Clouds are a Mother”: “Everything softer in the rain. The steel / swaddled in clouds. The skin of the brick / cottoned, the sky swollen.”

Ultimately, these are poems about change and growth, about how the act of remembering becomes an act of self–making, even an act of play. Recognizing, of course, “play changes / as you age, dolls and wooden spoons become stillness and light, / silence, a deep winter morning and the time to observe it.” For the poet, observation is joy. Comfort the Mourners reminds us that poetry remembers and remakes, that pain and beauty are often attached, and that for all of us, past and present are one and the same.

—Mike Bove

Slow Motion Grief

By Charlotte Matthews

My mother’s been gone longer

than my daughter’s been alive,

and still she visits me in office waiting rooms.

At MedExpress she sent a text saying

she was sorry she’d missed my call,

but she’d been at the movies.

It was a misdial, of course,

written by someone else’s mom,

but I allowed myself to briefly believe

she’d been in the shroud of a matinee,

tucked out of the hot June sun.

In that same office she appeared

in a photograph of a screech owl — wise bird,

perfect fit. I’ll never know why she didn’t tell

me she was sick. But when she checked

herself into the hospital to die, she folded her pants

and shirt so neatly before tucking them

into the plastic drawstring bag, I couldn’t bear

to take them out for a very long time, meaning

for years. The bag sat on my closet shelf

where it stunned me every single day.

I’ll never know what she had on her mind

before the morphine drifted her away.

A crater is a bowl–shaped cavity in the ground

or on the moon, caused by impact of a celestial

body. Isn’t that what grief really is?

A cavity, an emptiness that can never be filled.

Passing Angel Housekeeping

By Charlotte Matthews

My daughter calls as she walks

the dark winter streets to her

twelve–hour shift in the ER,

and I can hear the swish

of passing cars, the clicking

of the crosswalk light. Soon she’ll be

in triage or trauma or peds,

but for these few minutes she’s all mine

again, telling me more about Angel

who mops and disinfects the floors,

wipes down the walls after she

empties a room, telling me he is

at this moment on the other side

of the street, a shadow in circles

of lamplight. We’ve made up a life

for him, apartment on Grove Street

with pepper plants thriving

on the balcony, soccer on the TV,

English lessons from his kids,

church on Sundays. But none

of this we can ever really know.

In a few minutes Angel will guide

his push broom with such care and

precision it’s clear he is rowing

the boat that will take patients

back home to safety once again.