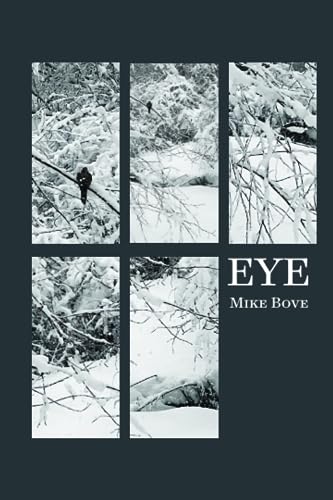

Eye

Eye, by Mike Bove.

Spuyten Duyvel, 2023,

94 pages, paper, $17,

ISBN: 978–1–959556–80–0

Mike Bove’s third collection of poems, Eye, carries two epigraphs: a notice in the Portland Press Herald of an impending early March snowstorm and this quote from poet Charles Simic: “Imagination doesn’t create. It sees connections to what is already there.” Together, these citations provide a nice set–up for what unfolds in the 51 poems that follow: encounters with a winter blast and the visions that emerge and ensue.

Snow–related poems abound. In “Plow Drivers” Bove pays tribute to the folks who clear the streets and their “angel’s wing of steel” which “descends to the road / in the sacred name of / clearing and passage.” Another poem, “Thundersnow,” draws attention to the phenomenon of rumbles in a snowstorm.

the sky in storm is worth our pause

there are things in nature

we rarely see despite hearing

stories and when at last we do

no matter for god or thunder

reverence is reverence

“Empty Churches” evokes a retreat from the blizzard. The final lines might be a summary of Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going”: “if you want to learn / what wonder is // find an empty church / and leave it.”

In amongst these snowbound reflections Bove conjures the past. The remarkable “Field Guide to Roadside Geology” contains several vivid memories: falling from a shopping cart — “my poor little self that once knew freedom / thereafter broken” — mining gemstones in Maine’s western mountains, and finding “treasure jewels” in sandy rivulets while lying in the street after a heavy rain. Pain and beauty go hand in hand here.

A number of poems relate to sight and seeing. In “Emily Dickinson Upstairs,” Bove revisits the story of how the poet almost lost her vision, a brush with blindness that ends with

the triumph of light

when the words did appear

and she spoke them out

in that sun–bright room where

sight had turned to song

Bove substitutes “eye” for “I” in a number of poems. As he explained in an interview with Jefferson Navicky in Hole in the Head Review, “‘Eye’ in some of the poems becomes a stand–in for our remembering selves.” So it is in the poem “Borderland” where the “eye” acts as a kind of distancing mechanism for dealing with a father who instilled fear in his son: “when he got old / eye / understood // better // who he’d been // and why he / loved // and who.”

Bove’s poems are often spare, with a Williams/Creeley/Levertov quality to the way the lines tack down the page. Here’s the ending of “Get Down,” inspired by wind in the trees:

it’s a woodland soirée

a deciduous two–step

and the wind sets

the tempo to arrhythmic

shuffle and who cares

that no one else

can hear it

just because

they can’t

doesn’t mean

it’s not music

In an afterword, Bove notes that the poems in Eye were written over five days “immediately before, during, and after the last major snowstorm of the year.” His “mind of winter,” to borrow from Stevens’s “The Snow Man,” leads to some beauties, including “Mourning Dove,” “Out,” “Outage,” “Tree,” “Walking at Night,” “A Boy Implores,” “Night Manager,” and “Warming Hours.” “Eye of the Storm” offers the best snowstorm advice:

rejoice and revel

claim this rapture

if you’d stayed inside

you’d have missed

this precious gift

of sight.

—Carl Little