Dwellers in the House of the Lord: A Poem

Dwellers in the House of the Lord: A Poem, by Wesley McNair.

David R. Godine Publishers, 2020,

66 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978-1-56792-663-7

When Maine Governor Janet Mills reads Wesley McNair’s poem “Seeing Mercer, Maine,” part of Maine Poet Laureate Stuart Kestenbaum’s “Poems from Here” Bicentennial video series, you feel like she knows the world and people he describes:

Would it matter if I told you

people live here — the old

man from the coast who built

the lobster shack

in a hayfield;

the couple with the sign

that says Cosmetics

and Landfill; the woman

so shy about her enlarged leg

she hangs her clothes

outdoors at night ?

And Mills does know this world: she comes from western Maine and has ridden those backroads where life is hardscrabble and fragile. McNair is a master of evoking that rural existence, right there with Baron Wormser, Elizabeth Tibbetts, Dawn Potter, Kate Barnes, and other poets who’ve lived in the back of beyond.

But in The Lost Child — Ozark Poems (2014) and the book under review, McNair moves into more personal, non-Maine territory, focusing on his kin with the same empathetic eye for those living lives “of quiet desperation,” as Thoreau put it. This time around, in a three-part narrative, he looks in on his younger sister Aimee.

McNair offers a devoted brother’s wrenching portrait of a woman — “a soldier against losses,” he calls her — suffering the indignities and cruelties of bad marriages and the shallow assurances of a megachurch offering “the five keys / to material happiness.” The course of Aimee’s life is jagged, ranging from the abusive — a husband who threatens to throw a hair dryer into the bath she’s in — and the suicidal — she leaps from the fourth floor of a building and survives — to the hopeful — two loving daughters — and the promising, a church where she feels born again:

I couldn’t help it, Wesley — Amen for the man,

and Amen for everybody around me in this church

out in nowhere, which felt like a loving mansion, too!

McNair also provides a portrait of Aimee’s husband Mike, a racist, gun-selling Trumper who nonetheless gains some redemption later in life. He “softens,” admits to having been an asshole, and becomes a lover of cats, which, according to his daughter Sophia, gives him “the permission to feel.”

Throughout Dwellers in the House of the Lord, McNair points out the villains. “It took only ten years for the new K-Mart Lawn / and Garden Center at the mall off route 89 to destroy / the nursery business my stepfather and my mother / had built,” he writes, highlighting the big box store scourge on small communities. He also presents the ugly rhetoric of Trump, who fuels the pall of hate that covers the country and seeps into his sister’s life. Referring to the president as “the damaged maestro / of nobody loves me enough,” the poet describes him showing off one of his executive orders “like Vanna White on a game show.”

In mid-July, Ted Kooser ran a six-line excerpt from McNair’s poem in his American Life in Poetry column:

I, too, am confused. I reach out

to the Mike who calls me

Buddy, the Navy name

for friend, and in every secret

phone call, I reach out also

to my sister, bereft and alone.

Even with the context provided in Kooser’s introduction, the lines seem somewhat random and hardly an engaging tease to reading the full poem. And yet they represent a central theme: a sense of confusion that the poet — and we — feel at the way the world careens, the severe ups and downs, the changes of heart, good and bad, and the judgments of the times.

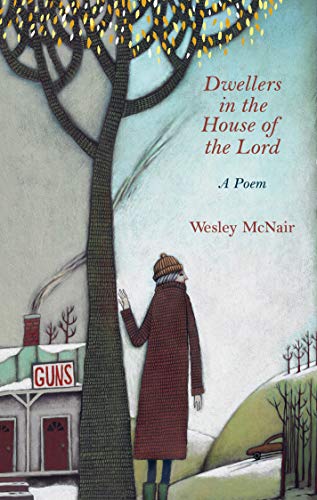

The cover bears out the truth of the classic admonition of not judging a book, etc. It’s somewhat misleading, a kind of Barbara Cooney / Will Barnet-blend vignette by Robert Brinkerhoff showing a woman in winter garb standing by a tree with a gun shop off to the side. It represents a setting in the poem — Aimee’s husband Mike’s place of business — and also illustrates an especially loving passage in the poem:

Then I see Aimee, standing by herself

in a cap and overcoat under the high, leaf-filled

branches of her favorite tree, a study in

winter and faithfulness, waiting, like me,

after all these months of her struggle, to be held.

McNair has always managed to insert some humor in his poetry, not LOL but a kind of wry eye for our foibles (a favorite example is “Hymn to the Comb Over.”) There’s little of that in Dwellers in the House of the Lord. While we might miss it, the times, the poet seems to say, call for a more sober approach.

Different stanzaic forms, including couplets, three-liners, and longer blocks, help propel the verse and the story. Other writers are no doubt shaping accounts of this era in their own fashion. They might look to McNair to understand how one can present with personal passion lives in the “arc of the hope of belonging” in an unprecedented moment in American history.

— Carl Little