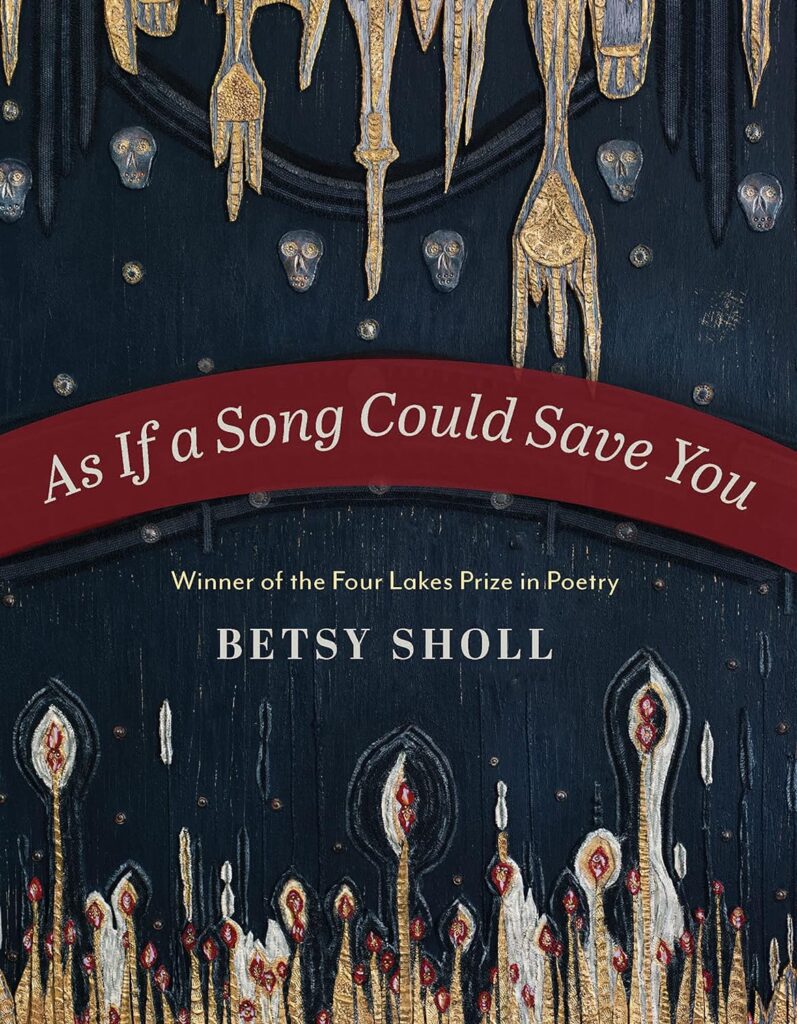

As If a Song Could Save You

As If a Song Could Save You

by Betsy Sholl

University of Wisconsin Press, 2022,

113 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 9780299340742

Betsy Sholl’s new book, her 10th, echoes many themes from past works — the connection of family, music (jazz), religion, and the natural world. And yet this book presents a different perspective: it is a reckoning, of sorts.

The book is dedicated to her husband Doug, who passed away during the COVID pandemic, and is presented in four sections. The title comes from a poem called “Bear,” early in the first section, in which, while jogging in New Hampshire, the poet encounters the creature feeding on berries with her cub in tow:

. . . and you’ve been warned:

sing, make a racket, till they shamble off.A barroom ditty comes to mind

all those bottles of beer on the wall, so you singas if a song could save you,

And the song does, in these grappling, emotionally connecting poems, offer a saving grace. There are a lot of recurring characters — Dante, Thelonious Monk, and her sister, alive, from the grave, and back. God and his entourage (Jonah, Job) show up a lot, which is the gut from where a lot of the poet’s grappling and reckoning comes. And all with an underlying percussive musical motif.

The ladder is a recurring image in this collection, especially in the poems “Ladders of Paradise,” and “On Ladders, Mystical and Otherwise.” Rungs of striving, deserving, and falling– off are all met in these places. “On Ladders, Mystical and Otherwise” is the longest poem in the book, comprising five pages and six sections. In section three, the ladder morphs into a chair

. . . up to the shelf where the forbidden sweetness

was hid, my own risk of teeter and fall.some wanting that’s hard to shake off,

hint of pleasure flickering, and that longing

to rise, or raid whatever’s out of reach.

The climb becomes shattering in the fourth part of the book, where the author introduces her husband in his declining state, the aftermath of his passing, and her own personal struggle with the loss. In the last line of the poem “One Step” — which describes the challenges of getting him ready for bed — the poet asks her husband if he needs help buttoning his night shirt:

Do you want help buttoning?

Not yet, he says. Not yet.

And what comes in successive poems is that reckoning, that gut– worn evolution of grief into wanting to live again, albeit with loss.

The next to last poem in the book, “Miserere Mei, Deus,” is the emotional apex of this journey. The song is a setting of Psalm 51 by Italian composer Gregorio Allegri, where the poet finds herself in an air cathedral:

. . . I am willing to toss

myself like bones into the future’s pot,

willing to say, Yes, oh secret heart,

as the sky lightens, Yes, to the mercy

that only comes when misery cries out.

The poem “His Shaving Cuts” concludes the book, as the lost husband suddenly appears in the aftermath of a huge snow storm, as

. . . he stands in the doorway

under the skylight in a freak shine of sun

and he proclaims the day to be a snow day — school’s out — and he heads forth into the white on his cross–country skis:

This is the kind of breaking and entering

I can take. Him stepping into snowshineeven if it so welcomes, so blazes around him

there’s no way back.

And this is the place where grief skates off, where the glass, seen through darkly, finds some life and light at the end.

— Craig Sipe