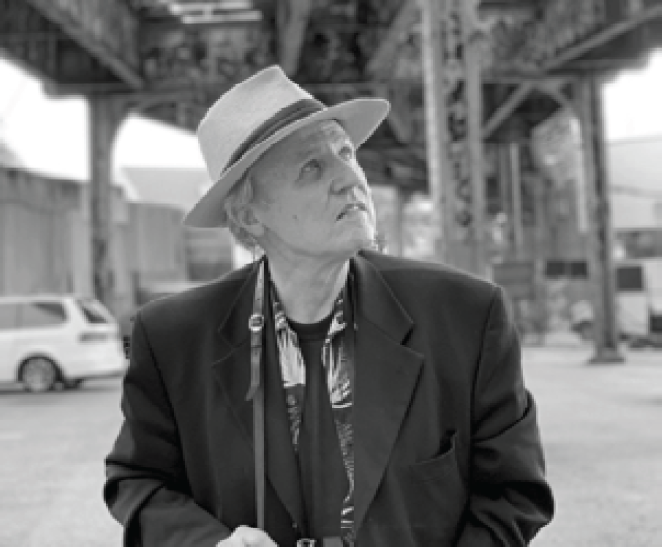

Gerard Malanga Interview

Interview with Gerard Malanga

conducted by Steve Luttrell

transcribed by Roger Dutton

Steve Luttrell: Gerard, I know that you were born and raised in the Bronx, and I wonder, how you think that New York City has come to inform and influence your work?

Gerard Malanga: Well, it wasn’t so much that NYC informed or influenced my work. It all started in the Bronx. It was around 1954 Christmastime that my dad gave me a present under the tree of a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye camera kit with flashbulbs and all and I started taking random shots of my surrounding neighborhood. But the major breakthrough occurred when several months later I read in the newspaper that the Manhattan portion of the 3rd Avenue El was going to be demolished, and I convinced by dad to chaperone me on the El’s last day in May and accomplished the unthinkable of documenting that day riding in the front car and shooting through the window during the rush–hour.

SL: I would be interested to know what it was like to have Daisy Aldan for a high school teacher? As she was a very well known editor of the Folders poetry series. I wonder if she invited well known poets to speak to her class? She must have been an inspiration to you.

GM: Daisy Aldan was like no other teacher I ever had nor ever will. Officially, she was my senior class high school English teacher. She was my first mentor. She introduced me to the world of poetry; and I realized then, that I wanted to be a poet and not some graphic artist on Madison Avenue and this would be my lifetime commitment. This was my future. Part of the unofficial curriculum was her contacts in the poetry world. She invited a number of poets to read in our class. This was a first instance of poets who were a living–breathing example of those who read in our class: Anais Nin, Kenward Elmslie, Jack Hirschman to name a few. When my junior year concluded, I had no idea whom I would be getting for an English teacher. Had I been assigned someone other than Daisy, it would be the razor’s edge for me. I believe in fate and I was fated to be her student. My guardian angel was looking after me that day. Daisy and I remained friends for life.

SL: I know that you were introduced to Andy Warhol by Charles Henri Ford. I wonder, who introduced you to Charles?

GM: I first came across the name Charles Henri Ford in Daisy Aldan’s anthology, “A New Folder,” sometime in April 1960 when I was still a student of Daisy. He’d been included as an artist with a pen and ink reproduction; not as a poet. I knew nothing about him at the time, but it’s a name you don’t forget. About a year later, while visiting with Willard Maas and his wife, the filmmaker, Marie Menken — my second mentors — Marie announced that Charles Henri Ford was paying them a visit. So on that afternoon encounter, Charles and I struck up a friendship. He invited me to come visit him at his penthouse studio in the Dakota and of course I took him up on the invitation and from that point on we became fast friends. We’d take in a movie from time to time, especially the B flicks down in Times Square, or attend gallery openings together. And, of course, he was the catalyst who brought Warhol and I together back in 1963. It was a friendship that lasted nearly 40 years.

SL: I know you’ve taken many photos over the years. So I wonder if there was anyone you wanted to photograph and never got the chance to.

GM: There are several, but I won’t go down that road because there’s no way to reverse time to turn those wishes around.

SL: I see where one of your earlier books, Wheels of Light, was printed in Tibet. Could you tell me how that came about?

GM: Wheels of Light was not printed in Tibet. I wish it was. It was actually printed in Dharamsala, in India, home of a Tibetan community headed by His Holiness himself, the Dalai Lama. I was on my way to Kooloo by bus and was looking at my map and I saw that Dharamsala was on the way, so I got off not knowing a soul. I never got to Kooloo, but signed up for a course in Tibetan Law and Philosophy taught by one of the Dalai Lama’s teachers who didn’t speak English but a younger Tibetan priest translated his very words in class. I’d been keeping a notebook of these minimal poems along my travels and I thought what better way than have them printed to commemorate this journey which brought me halfway around the world and at this point I hired these local Tibetans who ran a press. In the meantime, I signed up for an audience with His Holiness and when the day arrived I walked halfway up the mountain, but a monsoon hit and when I arrived at His Holiness’s doorway he and his male secretary took one look at me dripping wet in my see–through outfit, said “Come in. We’ll put you next to the radiator.” Anyway, a 15–minute audience lasted a full hour. In the meantime, His Holiness read the entire Wheels of Light right then and there. I’d prepared a special copy for him bound in yellow silk, his official color. He then said to me, “I own the press.” We had a hearty laugh. I didn’t know. One surprise led to the next. I suggested he address the General Assembly. He hadn’t been to New York yet. This was 1972. I think years later he did just that. When I departed Dharamsala a month later, I traveled by train on a 3–day journey to Pondicherry outside of Madras looking for buddy Angus MacLise, only to learn later that he and Hetty, his wife, had gone on to Kathmandu. It would be a year later that I caught up with them when I arrived back in the Berkshires. This whole journey which took two years on a one–way round–the– world ticket was inspired by Carlos Castenada’s first two books which had a big effect on my life back then.

SL: You mention the poet Angus MacLise. I know he was a good friend of yours and you were the editor of a book called The Brief Hidden Life of Angus MacLise. Can you speak about that project?

GM: Sure. It’s hard to know where to begin. Angus seemed to be everywhere and nowhere. He was a bit of a phantom. In the vernacular, he was one cool dude, 6′ 4″ and very cool–mannered, even when he spoke and, of course, he was multi–talented, both as a musician and as a poet. The Brief Hidden Life of Angus MacLise is really the title to an extended essay I wrote that was also the focus of the chapter in my unpublished manuscript of memoirs. His own publications are far and few between. Very scarce. Part of the problem, if I can call it that, is that his poems are very long tracts. Our mutual friend, Piero Heliczer, brought out a slim volume of poems under the imprint of “The Dead Language” which Angus figured in as a co–founder. He and Piero brought it out when they were living in Paris. This would’ve been around 1958, I believe. I produced a double CD of choice Angus musical tracks released by Sub Rosa around 2002. That’s pretty much the extent of it and at this point in time I wouldn’t call these titles exactly “recent.” In 1982, I was commissioned by the Dia Art Foundation to collect all and everything having to do with Angus. I hired a sound engineer to re–mix the analog tapes which a mutual friend, the photographer Don Snyder, had stored in a clothes closet for safe–keeping when Angus hightailed it to Kathmandu. So thank God that’s where they were when I got this project underway. I still maintain a duplicate set of the tapes in cassette format. I also have the largest collection of Angus in photographs. The project you mention was basically a guideline if and when I found a publisher, which hasn’t happened yet. Dia was expecting to publish the Collected Poetry, but then they bowed out, focusing instead on supporting the artists they already had in their stable. I also compiled a Collected Checklist which I copyrighted. So it’s a little bit here, a little bit there. I gave LoveLove magazine a short poem for their next issue. They’re based in Paris. I serve as the magazine’s mentor.

SL: In your book AM: Archives Malanga, it mentions (in vol.1) that you did an interview with Salvador Dali. How did that come about and what your memory of it now?

GM: Actually, the interview appeared for the first time in the Sparrow pamphlet series published by black Sparrow Press. I think it was in 1969, shortly after I conducted the interview. The previous year I acquired an Aguilar Spanish edition of Lorca’s Complete Works at Rizzoli bookshop. The book bound in beautiful leather runs nearly 2000 pages. When was I ever going to see another copy just like it? So I sprung for it. Upon flipping through its pages, I was intrigued when I discovered this photo of Lorca and Salvador Dali as classmates at an art school in Madrid. I had no idea they were friends. In fact, they were a triumvirate that also included Luis Bunuel. Since I was close with Dali, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to interview him about his friendship with Lorca. As far as I could tell, this was a side of Dali that had never been explored. So I arranged for us to meet at this health food restaurant called Brownie’s on East 16th Street, just down from Union Square. We had lunch and he was his usual convivial self, cracking jokes and talking in the third person, like Dali this and Dali that. I felt a side of him was greatly misunderstood. Dali was actually an extraordinary intelligence with a great sense of humor and he was always gracious with me. I taped him during lunch. It’s not a very long interview, but enough was said to give a sense of what they were like together as students.

SL: In your newest book of poetry, The New Melancholia, it seems the poems are portraits. Portrait Poems /of friends and loves. You said that you “characterize my work as love poetry.” These poems are a “gift of Love.” Can you expound on this a little?

GM: Yes. The New Melancholia as a book of collected work over the past 3 years is an assembling of love poems or portraits of love. I find it difficult to “expound” on what we’ve been discussing because as I understand it, to “expound” is to “explain.” To me, it doesn’t make any sense to explain about love. Let the poems do that. In order for me to write the poems that comprise this book, I have to love my subjects, whether they’re alive or dead. I’m channeling “love” through the poems to the subject of the poems and one of the ways that I do this is through accessibility. The poems MUST be accessible to reach the reader and so for a poem to convey that love, is by being accessible. Love reaches the reader and through the reader back to the subject. Of course, I’m not carrying these concepts in my head while writing these poems. I make myself aware of this because I put myself in a trance. In effect, I’m placing myself in a “stream of consciousness though even here, it’s not “consciousness” per se, but an instance of stream of the unconscious; and that’s how all the elements cohere while I’m in the process of writing the poem. Poets who decide, Oh, I’d like to “write about that tree outside my window” are kidding themselves because the poem comes out as a ready–made with no contact with consciousness and I find it to be an insult to the language. The true test of poetry for me is if I can get past the first line. As soon as I see a poem broken up into sections with section titles or numbers, that’s all so narcissistic. That’s showing off, like “look at me.” I wanna say, you forgot to take your meds! Go back to sleep! Ted Joans is a perfect instance of always in the groove when writing and I’m always trusting my instincts. Same thing.

SL: How did you come to title your book The New Melancholia?

GM: I can’t remember when The New Mélancholia title originated. It had to be around the time Bill Roberts, my publisher, and I started proofing drafts for the manuscript; my guess around mid–summer 2019. I’d been toying around for a title that included the word “melancholy” when I purchased this post card poem from a book dealer which my friend, Piero Heliczer, had set to letterpress in the late 1950s under his imprint, “The Dead Language,” of a short poem by his father–in–law written in French and titled The New Mélancholia with an accent mark on the “e.” A friend of mine fluent in French tried to correct me because it wasn’t correct French, even though the book title was in English, but I went ahead anyway because I have this tendency of breaking rules, especially if it has something to do with poetry, and besides, Piero’s father–in–law also adopted that format. My reasoning was that the accent mark added a colorful touch to the English title, even though the word is French.

SL: In any interview with you, it becomes difficult to know where and when to stop and end it. Your experiences cover so many different creative areas but in closing I would ask, what’s next for Gerard Malanga? What are you presently working on?

GM: Well, I guess the easiest way of approaching what I’m presently working on is what I’m into at this very moment. Last February I adopted Odie, a black domestic shorthair feline with a very colorful history. He’s twenty–years–old, born cross–eyed with perfect vision. Lost his tail to some mysterious infection a year ago, so now he passes for a Manx, and he’s deaf. We communicate by sight and human touch and feeling. Right now I’m creating an assemblage of 30 or so small pictures I shot of him surrounding one big central portrait, all taken in front of my living–room window by the sofa; and because the piece was partly inspired by a Duchamp silhouette cut–out in profile which he made in 1958, I’m calling our piece “Odie as Duchamp portraits in profile.” I’ve even created a rubber stamp giving him co–credit as collaborator. Odie is a sentient being and I love him dearly and I know the feeling is mutual. It will be a 24 x 20 inch piece in an edition of twelve hors commerce. My second project is a limited edition portfolio box titled “10 Musicians” which Bill is designing in an edition of ten which should be ready hopefully before the year is out. This is enough to fill my plate. I had to cut back on an exhibit for the present. I like to keep my working habits simple. Otherwise I might lose focus. On top of everything else, happily the poetry continues, so there’s no confusion there. I’m averaging a couple of poems a week and I’m very brutal when it comes time to put a book together.

SL: Gerard, what would you say is the role memory and active imagination plays in your poetry, and do you find it to be a channel to your “inner child”?

GM: I was always artistically inclined when I was a kid. Emma, my mom, used to tell the neighbors that I could “draw from memory,” which was true. I used to do these continuous drawings on separate sheets of paper depicting what’s called a “Cross– section” of a subway station and on the street above lined with neatly–drawn lampposts and signage and I would tape the drawings together and run the scroll through our apartment to amuse myself. I think I was 10 or 11 when my parents signed me up for an arts and crafts class at the local YWCA after regular school let out just to keep me off the street. They were both working parents. It was at this class that I discovered my first instance of a photography experience with this book called “Metropolis” that the teacher had on a shelf with other books for the students to peruse. The book was basically a day in the life of a big city, but it was obviously New York. I later discovered that the book was published in 1932 which accounts for my perceiving that the pictures depicted a time, that time–wise, was somewhat remote. I would pour over it whenever I came to class and at the end of the term I charmed the teacher into letting me have it. I still have it. The experience was one of training my eye into taking pictures later on. I was good at remembering things. I knew all the stations on the “D” line whenever we traveled. I was really into trains and, of course, imagination and memory have always been present in how all this gets channeled into my poetry, especially when I’m writing about people I knew decades ago. I’ve been very fortunate in remembering as being prominent in my work.

SL: After you’ve made a poem do you re–work it at all, or is it a “first thought best thought” sort of thing?

GM: That’s an Allen Ginsberg adage, but what works for Allen doesn’t necessarily work for me. In principle, but try telling that to Jackson Pollock? I wonder if even Allen follows his own theories? “Howl” is riddled with revisions. Many years back I used to go through 4, 5, 6, 7 typewritten drafts; even a few times up to a dozen, until I finally got it right, but in the last twenty years or so I’ve gotten it down to 2 or 3 at most. Once in a while I worked it at just one draft. I like working on yellow legal size pads. It gives me more mental space. Always the first draft is handwritten followed by the first typed draft and then from there subsequently 1 or 2 typed drafts. Once I’m perfectly satisfied with where I’m at with it, I’ll commit it to a digital file. And even then I might make 1 or 2 minor changes, but that’s my method and it’s worked for me. After that I’ll read it aloud to myself several times during the night. Every line must have the perfect pitch. If there’s something off, I’ll find a way to make it sound right.