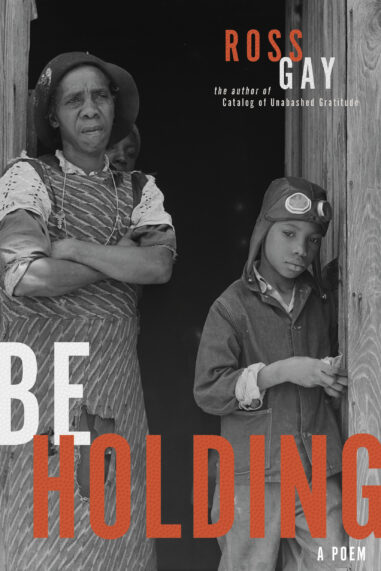

Be Holding

Be Holding

by Ross Gay.

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020,

109 pages, paper, $17.00,

ISBN 978-0-8229-6623-4

When I found myself playing basketball in the basement with the basket made out of a ping pong table and the action-figure-sized wrestling ring my father made for my brother and me, I practiced The Move, the stretched out, slow-motion focal point of Ross Gay’s book-length poem: Dr. J elevating and wrapping the ball around the backboard in the 1980 NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. Granted, when I practiced The Move, I was probably using a wiff le ball instead of a basketball, and my little brother was a much less imposing version of Lakers’ center, Kareem Abdul Jabbar. But I practiced the shit out of that shot.

And I have a feeling Ross Gay did too. Gay is an incredible poet, who is also an athlete (a former college scholarship football player), and an all-around lover of sports (he founded the online sports magazine Some Call it Ballin). That far-reaching love comes across profoundly in Be Holding.

However, it’s easy to miss that this book is about basketball. Dr. J isn’t mentioned in any of the blurbs on the back of the book, and neither is basketball. Claudia Rankine makes oblique reference to “the history of a game” in her blurb. It’s only the font of the book’s title that gives the reader a faint hint, and you have to look closely to even see it. The sans-serif font is made up of the same distinctive texture of a basketball: many tiny raised dots designed to make the ball easier to grip. As a basketball fan, I wondered why The University of Pittsburgh would make the decision to almost erase basketball from the book’s cover.

And yet, from a poetry perspective, I see why they made this choice. Although the book is deeply about basketball and Dr. J and the witnessing of his gravity-defying move, it is about much, much more than basketball. It is a book that ambitiously seeks to bring serious lovers of basketball and serious lovers of poetry together. And it’s this coming together, this beholding together — that’s where Ross Gay’s miracle resides.

Fittingly, this miracle of two entities coming together is a miracle in couplets. The book-length epic poem is a prolonged moment of wonder and witness that feels like the poet (and, through the act of reading, the reader) is holding his breath throughout the entire poem, extending the couplets in a moment parallel to Dr. J’s gravity-defying flight.

I am holding my breath

with this looking

and looking

And in this long-held breath, the long hours of the night pass throughout the poem: 1:48 a.m., 2:26 a.m., 2:59 a.m., 3:11 a.m., 4:56 a.m. The poet watches and re -watches over and over again the videoclip of Dr. J while slipping in and out of other far -reaching associations:

. . . when witnessing

the unwitnessable, the way

we do so often these days,

today, witness the unwitnessable,

my own palms twisted again and again

toward the earth,

witnessing the unwitnessable,

If the poem focused solely on Dr. J, I would love the poem, but it wouldn’t feel transcendent; I would feel satisfaction at a skilled poet rendering the art of basketball on the page (no small feat!). However, Gay does more than that — he witnesses the unwitnessable by blurring and expanding our vision. It’s not only beautiful, but also slightly unsettling, as only seems right when one witnesses the unwitnessable.

There are no breaks in this book-length poem, no section markers to indicate transitions, and hardly even moments of transition. One moment Gay is talking about Dr. J and the next he’s on to the Marlborough Street Fire photograph. If a reader doesn’t pay close attention, these abrupt movements could be quite disorienting; in fact, even if a reader does pay attention, they are disorienting. And that’s where the magic happens. Like watching for a magician’s sleight of hand, readers are stunned.

As the smoke clears, they wonder, how did he do that ?

As an example, let’s return to and then extend the above quote:

witnessing the unwitnessable,

which is not unlike their motion

treading water

in a college gallery

Poof! And he’s off into the world of photographs, in this case two Black people falling from a fire escape, a famous photograph that won the Pulitzer Prize for spot photography. Only gradually, or like a gradual bolt of lightning, did I realize that once again Gay was helping us witness the unwitnessable.

Towards its end, the poem, like Dr. J’s famous move, reaches:

we in here talking

about the reaching

that makes of falling flight . . .

talking about holding

our breath . . .

of being beholden,

talking about

how might I hold

my beholden out to you

The result is a magical wind. One might not think words could fly like this, but the couplets are like samaras, those little whirly helicopters from maple trees — and the falling flight is nothing short of miraculous.

–Jefferson Navicky