Woman Looking at a Vase of Flowers

Woman Looking at a Vase of Flowers, by Elizabeth Savage.

Furniture Press Books, 2017,

34 pages, paper, $12,

handmade limited-run chapbook.

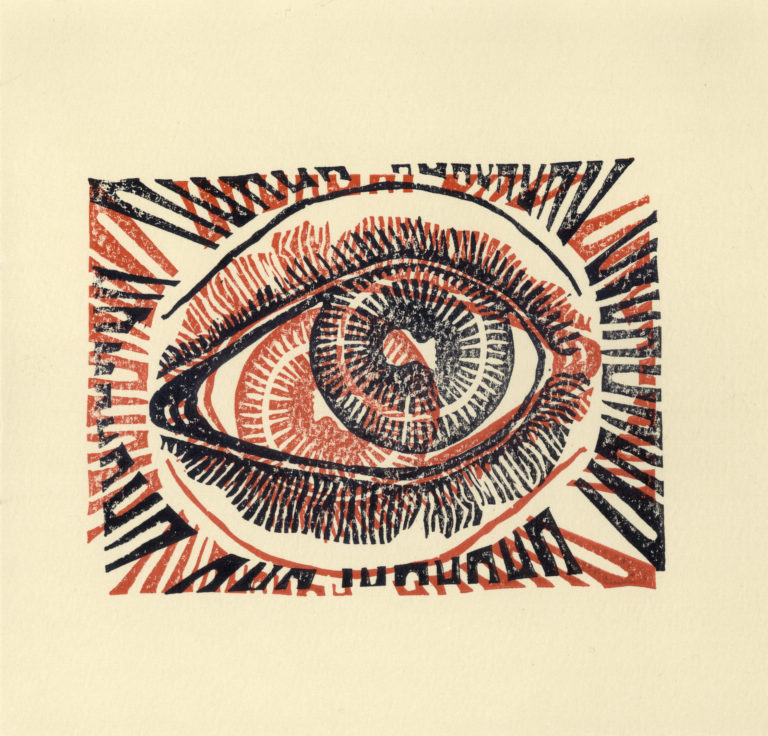

In her new chapbook, Woman Looking at a Vase of Flowers, Elizabeth Savage casts a simultaneously telescopic and microscopic eye on the act of observation itself. Each poem in the chapbook is named after a short phrase from Wallace Stevens’ poems “Woman Looking at a Vase of Flowers” and “On the Adequacy of Landscape,” both from Parts of a World. Just as the act of looking is fractured into kaleidoscopic fragments in Stevens’ original poems, Savage fractures the poems into their component parts, re-arranges them, and, in so doing, invents a new way of looking at looking—and at poetry—by moving through and within her sources.

Stevens’ poems play with the central natural elements of sun, sky, wind, and sea, as do Savage’s. The “inhuman owl” that begins the chapbook quietly wings through its entirety—an otherworldly symbol of change in motion, its hoot echoing from poem to poem. Savage calls our attention to the way the “people in the air” of Stevens’ poem gaze upon the owl. As they look, they are frightened by the owl—by how it looks back at them through its large eyes. The people in the air, Savage writes, “spy horizons//of what they are/exchanged/for worlds below.” In the end, though

“[t]hey seek this owl out in the night/to measure central things,” Savage shows us that we can never really see what we’re looking at:

When day is done

in towers tall

all birds are black

against the sun

Aesthetic grandchild of Lorine Niedecker and Gertrude Stein, Savage is tuned in to a “cosmic ear” and able to wield language with the precision of a scalpel. These gem-like little poems read like perfectly balanced equations for an experiment in language, with loving care imbued in each line. Every word is charged with its own polar magnetism, and they collide against each other in symphonic brilliance. Most poems resist narrative and syntactical completion, operating instead as pieces of sentences that twist in on themselves elliptically and start anew, like Escher paintings.

The acts of looking and listening become synesthetic experiences in these poems: “behind the iris/this fragrant song.” And as the senses meld together, Savage explores the acts of melting and

dissolution as “Jupiter/puddles/into Venus” and “her call /falls/ unbruised.” “[L]ive stillness/is flight,” Savage writes, guiding the reader through a mutable world of shifting winds and drifting night. Between all the simultaneity and mid-flight suspension is a calm balance: “Formlessness Became the Form” is the title of one poem; another ends, “strange/how change/enlightens.”

InWoman Looking at a Vase of Flowers, Savage juxtaposes that which shines against that which is foggy, that which is empty against that which is full. These poems interrogate transience versus permanence and are imbued throughout with a “barbaric softness” of contrasts and fluidity: “blue is/not blue/nor brass/ but flickering.” Savage is concerned with sound and silence, stillness: “even thunder/what wind dissolves.” Words flutter and shudder on the page with a delicate precision keenly aware of the movements of breath and mind, gazing and flight.

—Alyse Knorr