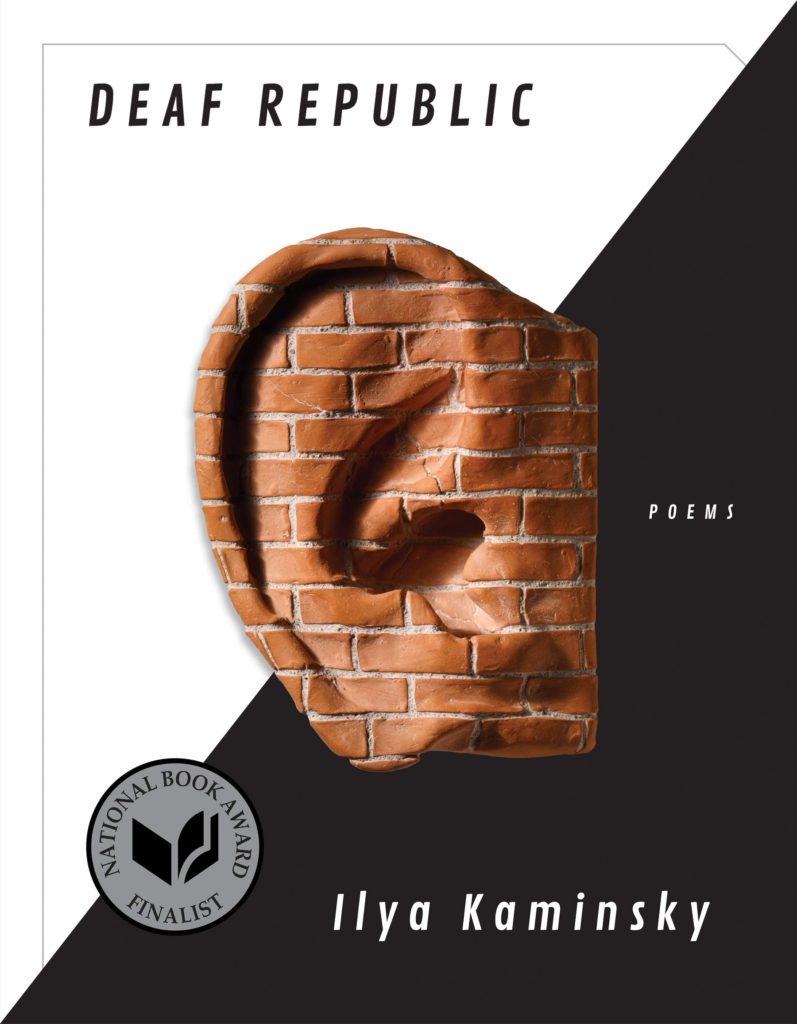

Deaf Republic

Deaf Republic,

by Ilya Kaminsky,

Graywolf Press, 2019,

96 pages, paper, $16.00,

ISBN: 978–1–55597–831–0

“Our country is a stage” begins act one of Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky, a collection of poems, presented in two acts, that operates as a parable and dark warning for our time. A script enacted in public and private spaces, the narrative unfolds in relation to an act of violence and an act of protest, of refusal: During a time of war, a child is shot by soldiers in a public square in the fictional town of Vasenka; and the next morning the townspeople wake and both refuse to hear the soldiers and refuse to speak, refuse in the name of the child. Standing up like “human masts — deafness passes through us like a police whistle,” reports puppeteer Alfonso Baribinski, the lead character in act one. The citizens then proceed to coordinate their dissent through an invented sign language that is illustrated throughout the book.

Born in the former Soviet Union, Ilya Kaminsky has a personal relationship with deafness. As a child, he lost his hearing due to a mistaken medical diagnosis. When Kaminsky immigrated to the United States with his family as a teenager, he was outfitted with hearing aids. He retains an ambivalence about his place in the hearing world; in an interview with the Guardian, he notes that “deaf culture is such a beautiful thing. It has one of the youngest languages in the world and is still developing.” Artistically speaking he believes the absence of language can be a powerful tool, and that “just a few words surrounded by space” can express deep truths. This ambivalence with regard to silence — its strengths and its dangers — actively shapes the book.

In “Gunshot,” the townspeople gather to watch Alfonso and Sonya’s puppet theater in the Central Square when soldiers arrive and order the crowd dispersed. Everyone freezes except the deaf child Petya who continues to giggle, even as the puppeteers use the puppets to mock the soldiers.

The sergeant turns toward the boy, raising his finger.

You!

You! The puppet raises a finger.

Sonya watches her puppet, the puppet watches the

Sergeant, the Sergeant watches Sonya and Alfonso,

but the rest of us watch Petya lean back, gather all

the spit in his throat and launch it at the Sergeant.

The sound we do not hear lifts the gulls off the water.

Silence riddles the poems with holes like the gunshot wound — deep pockets of unspeakable grief. And yet, Kaminsky notes, “The deaf don’t believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.” In Vasenka, after bombardments, the empty streets of the town are full with the squeak of strings and tapping of wooden fists and feet on doors — the citizens hang puppets on their doorknobs and out windows to signal an arrest in the family. We hear throughout these poems the eloquent speech of the body, of an open mouth, of hands and feet: We see in “Sonya’s open mouth // the nakedness / of a whole nation.” And when Alfonso runs, “etcetera with my legs and my hands etcetera I run down Vasenka Street etcetera — ” we understand the rattle of fear and the uneasy, breathless rhythm of feet, a body running in fear for its life.

Throughout the book hands play an important role in communicating — they are also, after all, the tools through which the puppet theater tells its stories — and in the resistance. In the book, Kaminsky teachers the reader the same sign language that the citizens of Vasenka invent and teach each other. Simple line drawings of hands — echoing drawings of the ASL alphabet — tell us “the town watches” or “army convoy,” “hide.”

In the second act, the insurgency is run by Momma Galya Armolinskaya, the owner of the puppet theater. Galya’s trick is to provide entertainment for the soldiers, nights of burlesque followed by sexual intoxication, that allow her to kill the men with puppet strings around their necks. And as the soldiers arrest someone, Galya instructs “his children’s hands to make of anguish // a language — / see how deafness nails us into our bodies.”

This “nailing to the body” is also expressed in beautiful love poems, where touch exceeds the power of language to communicate; a child is born, a couple takes a bath together. Within the surreality of the worsening situation, there is also beauty; great acts of tenderness are present, if fleetingly, in moments of calm. A poem toward the end of the book begins on balconies on a sunlit day; sunlight reflects off poplars, off a sleeping soldier, and off imaginary scissors as a girl pretends to cuts her hair. But the soldiers wake and gape: in “Firing Squad” they have discovered Galya’s tricks.

Tonight they shot fifty women on Lerna Street.

I sit down to write and tell you what I know:

a child learns the world by putting it in her mouth,

a girl becomes a woman and a woman, earth.

Body, they blame you for all things and they

seek in the body what does not live in the body.

Later, on Tedna Street only doorways are left standing, doors with a puppet dangling for every shot citizen.

The last poem in act two consists of only one line stretched across the page —

We are sitting in the audience, still. Silence like the bullet

that’s missed us, spins —

followed by four signs the reader can now translate, having learned the town’s language: “town,” “the crowd watches,” “earth,” “story.” Watching, like silence, plays an important if ambivalent role in the poems here, the role of witness facing the forking paths of action / inaction. While deafness by the fictional citizens of Vasenka is chosen as a form of resistance to forces beyond their control, this deafness does not rob the citizens of means by which to speak. In Deaf Republic, silence is also an indictment of our own political silences, our own refusals to speak or hear.

Two poems flank the book like bookends. They are placed in our own time, and we can recognize ourselves — a rich country in a “time of peace.” In the first poem of the book, We Lived Happily during the War, the speaker notes, “we / protested / but not enough, we opposed them but not enough.” Forgive us, it asks. In the final poem, you will perhaps recognize the man shot through the car window as Philando Castile, a boy shot and left on the pavement as Tamir Rice; you will recognize the ongoing brutal violence against our own citizens; Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many more. The speaker in this poem watches his neighbors open their phones to watch a cop demanding a man’s driver’s license. They then pocket their phones and go on with their lives.

I do not hear gunshots,

but watch birds splash over the backyards of the suburbs.

How bright is the sky

as the avenue spins on its axis.

How bright is the sky (forgive me) how bright.

What happens to our language in times of crisis? Kaminsky tells us: our silences still have volumes to say.

— Julie Poitras Santos